Abstract

The European Union's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) compels trading partners to confront a fundamental strategic choice: how to respond when external regulatory pressure collides with domestic institutional realities. Three distinct strategic archetypes emerge from national responses. China pursues defensive adaptation, constructing parallel carbon accounting systems that satisfy international requirements at interface points while preserving core domestic institutional arrangements. Turkey exemplifies dependent integration, achieving regulatory alignment through wholesale adoption of EU frameworks at significant cost to policy autonomy. India demonstrates negotiated autonomy, building domestic carbon market infrastructure while simultaneously contesting CBAM's legitimacy through diplomatic channels. These divergent pathways reflect the interaction between two structural variables: path dependency coefficients (ρ) measuring energy system rigidity, and trade exposure intensity determining bargaining leverage. Drawing on institutional economics and the carbon lock-in literature, we theorize that path dependency operates through three reinforcing mechanisms: increasing returns from sunk investments, institutional complementarities across governance domains, and political coalitions defending incumbent arrangements. Turkey's ρ≈0.65 indicates severe coal infrastructure lock-in that constrains decarbonization speed regardless of policy ambition. India's lower EU trade dependence (13% of exports versus Turkey's 41%) creates strategic space for diplomatic resistance. China's institutional path dependency in park-level industrial governance generates different constraints than energy infrastructure, enabling technical sophistication alongside institutional misalignment. The analysis yields three testable propositions linking structural position to strategic choice, providing a falsifiable framework for understanding emerging economy responses to transboundary carbon regulation. The three archetypes carry distinct implications for global carbon governance: defensive adaptation may fragment international carbon accounting into incompatible regional systems; dependent integration creates asymmetric adjustment burdens favoring regulatory origin countries; negotiated autonomy challenges the legitimacy of unilateral border measures while potentially reshaping multilateral climate frameworks.

1. Introduction

On an autumn day in 2024, a compliance officer at a major Chinese steel exporter confronted an unexpected paradox. Her company's Continuous Emissions Monitoring System produced data more granular than many German competitors could generate. Yet when completing CBAM transitional declarations, she found herself checking the box for "default values used" rather than "facility-specific data submitted." The monitoring equipment worked flawlessly. The problem lay elsewhere, in institutional architectures that channeled precise measurements into accounting frameworks incompatible with European requirements [1].

This scene plays out across industries and borders as the European Union implements CBAM, transforming carbon data from environmental reporting into trade prerequisites. The choices they make reveal fundamental strategic calculations about sovereignty, market access, and the acceptable costs of regulatory alignment. Some nations rush toward harmonization. Others resist and contest. Still others construct elaborate workarounds that satisfy surface requirements while preserving domestic arrangements. Understanding these divergent responses requires moving beyond technical compliance assessments to examine the political economy of institutional adaptation under external pressure.

CBAM entered its transitional phase in October 2023, requiring importers to report embedded carbon in covered products including steel, cement, aluminum, fertilizers, and electricity [2]. Full implementation begins in 2026, when importers must purchase certificates corresponding to the carbon price that would have applied had products been manufactured under EU Emissions Trading System rules. For countries exporting carbon-intensive goods to European markets, this mechanism creates powerful incentives to demonstrate low carbon intensity through verified facility-specific data, since EU default values deliberately penalize incomplete information [3].

The resulting compliance pressure operates unevenly across the global economy. Countries differ in their existing carbon accounting infrastructure, their trade dependence on EU markets, their energy system characteristics, and their diplomatic leverage in bilateral negotiations. These structural variations generate distinct strategic imperatives. A small economy sending half its exports to Europe faces different calculations than a continental power with diversified trade relationships. A nation with mature carbon pricing mechanisms confronts different options than one building climate policy from limited foundations. An economy locked into coal infrastructure operates under different constraints than one with flexible energy systems.

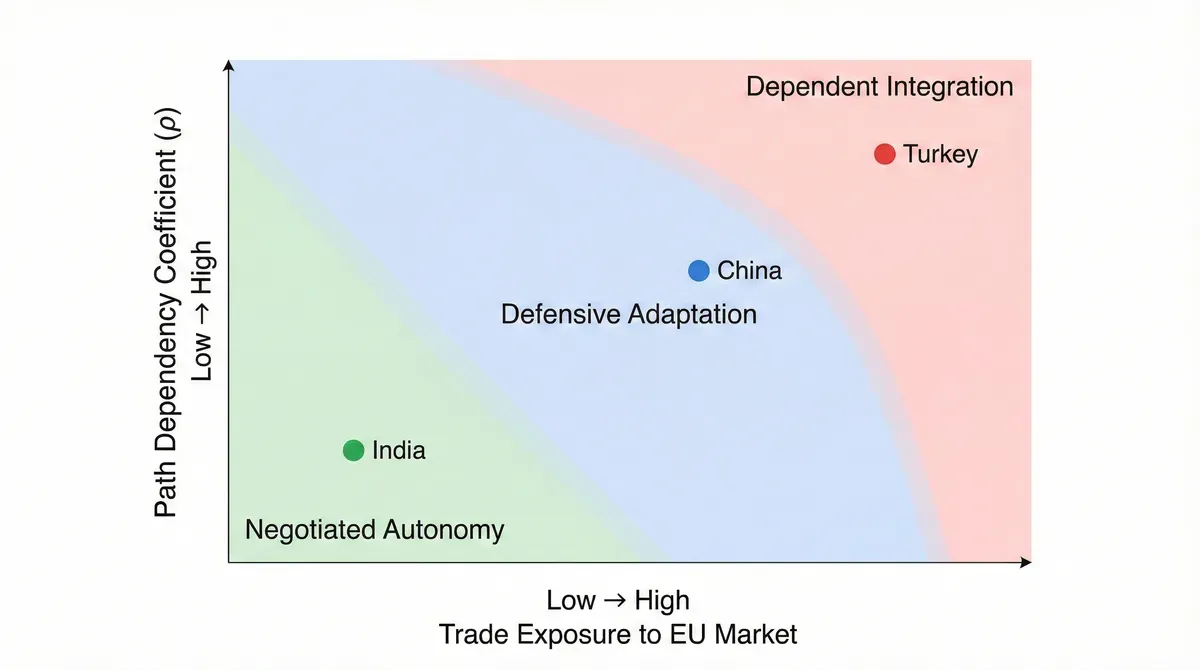

This study develops a framework for understanding how structural position shapes strategic response to transboundary carbon regulation. We identify three archetypal strategies: defensive adaptation, dependent integration, and negotiated autonomy. Each archetype reflects a coherent logic linking structural conditions to institutional choices. By examining how China, Turkey, and India navigate CBAM pressure, we illuminate the mechanisms driving strategic divergence and assess implications for global carbon governance evolution.

This study makes three moves. Empirically, we trace how China, Turkey, and India actually responded to CBAM between 2020 and 2025, drawing on policy documents, trade statistics, and institutional assessments. Theoretically, we ground path dependency coefficients (ρ) in the institutional economics literature, specifying the micromechanisms through which lock-in constrains strategic choice and deriving testable propositions about the ρ-exposure interaction. For policy, we challenge the assumption that successful adaptation models transfer across differently positioned countries; what works for Turkey may trap India, and vice versa.

2. Theoretical Framework: Path Dependency, Trade Exposure, and Strategic Choice

2.1 The Strategic Trilemma under External Regulatory Pressure

Countries facing CBAM pressure confront what we term a strategic trilemma among three objectives: maintaining market access to European Union markets, preserving domestic policy autonomy in carbon governance design, and minimizing economic adjustment costs during transition. Complete achievement of all three objectives proves impossible. Regulatory harmonization with EU standards secures market access but sacrifices autonomy and may impose substantial adjustment costs. Resistance preserves autonomy but risks market exclusion. Gradual adaptation attempts to balance objectives but may achieve none fully.

The trilemma's resolution depends on two structural variables that constrain available options. The first is path dependency, which we formalize through a coefficient ρ measuring the rigidity of existing systems relevant to carbon performance. The second is trade exposure intensity, capturing the degree to which EU market access represents an existential economic interest versus one interest among many.

2.2 Theoretical Foundations: Institutional Change and the Micromechanisms of Lock-in

The path dependency concept animating this analysis draws on three decades of scholarship in institutional economics, evolutionary economics, and political science. Grounding our framework in this literature clarifies the mechanisms through which historical choices constrain present options and specifies conditions under which lock-in proves more or less binding.

Increasing Returns and Technological Lock-in. Arthur's foundational work on increasing returns demonstrates that early advantages in technology adoption can become self-reinforcing, eventually locking systems into particular trajectories even when superior alternatives exist [4]. The mechanisms driving increasing returns include large setup or fixed costs that decline with scale, learning effects that improve performance through accumulated experience, coordination effects arising when adoption by others increases value, and adaptive expectations where prevalence signals likely persistence [5]. Applied to energy systems, these mechanisms explain why fossil fuel infrastructure exhibits remarkable durability: power plants represent massive sunk costs recoverable only through continued operation; operational learning accumulates around existing technologies; grid infrastructure coordinates around incumbent generation sources; and investment expectations assume continued fossil fuel dominance.

Institutional Complementarities. North's institutional economics extends lock-in analysis beyond technology to formal rules and informal constraints governing economic activity [6]. Institutions exhibit path dependency because they develop complementarities with other institutions, creating interdependent systems where changing one element requires costly adjustments elsewhere. Carbon accounting frameworks exemplify such complementarities. China's facility-level emissions reporting integrates with enterprise performance evaluation systems, regional development planning, and state-owned enterprise governance. Shifting to product-level accounting, as CBAM requires, disrupts these institutional complementarities, imposing coordination costs beyond the direct technical adjustments involved.

Political Coalitions and Distributional Consequences. Pierson's application of path dependency to political institutions emphasizes how policies create constituencies invested in their continuation [7]. Carbon-intensive industries generate employment, tax revenues, and regional development that mobilize political resistance to rapid transformation. This political economy dimension means that even technically feasible transitions face organized opposition from groups bearing concentrated costs while diffuse benefits remain politically underweighted. Turkey's coal mining regions exemplify this mechanism: employment in Zonguldak and Afşin-Elbistan creates constituencies whose political influence shapes national energy policy regardless of climate commitments [8].

Carbon Lock-in as Compound Constraint. Unruh's concept of carbon lock-in synthesizes these mechanisms, arguing that fossil fuel dependence persists through mutually reinforcing technological, institutional, and political systems forming a "Techno-Institutional Complex" [9]. This framework proves particularly relevant for understanding CBAM responses because it identifies multiple, interacting sources of rigidity. A country might overcome technological lock-in through equipment imports while remaining trapped by institutional complementarities. Another might reform institutions while political coalitions block implementation. The compound nature of carbon lock-in explains why policy ambition often exceeds realized transformation.

Implications for Strategic Choice. This theoretical foundation generates specific expectations about how path dependency constrains CBAM response strategies. High-ρ countries face not merely technical obstacles but interlocking constraints across technological, institutional, and political dimensions. Breaking lock-in requires simultaneous action across multiple domains, a coordination challenge that external pressure alone cannot resolve. Countries with lower ρ possess greater strategic flexibility not because they lack constraints but because their constraints operate more independently, permitting sequential rather than simultaneous resolution.

The literature also suggests that path dependency is not absolute. "Critical junctures" can destabilize existing arrangements, creating windows for institutional change [10]. CBAM may function as such a juncture for some countries, providing external pressure that tips domestic political balances toward transformation. Whether it does depends on the interaction between external pressure intensity (trade exposure) and internal system rigidity (ρ), the core relationship our framework formalizes.

2.3 Path Dependency Coefficient (ρ): Quantifying Structural Rigidity

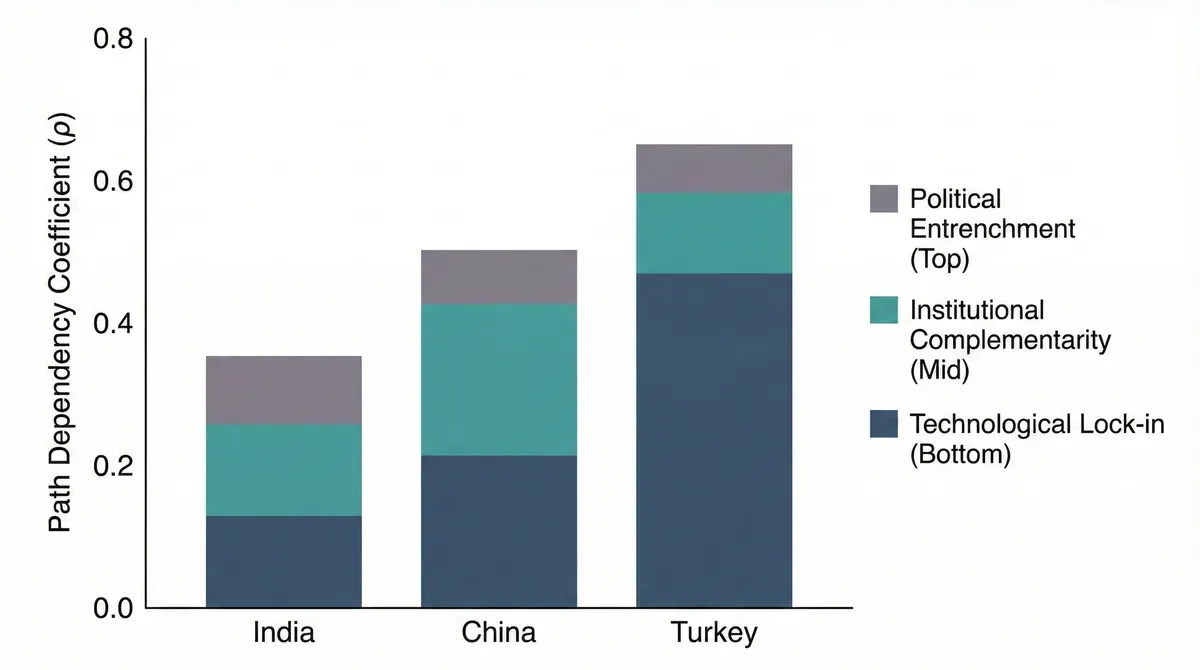

Building on these theoretical foundations, we conceptualize the path dependency coefficient ρ as a composite assessment ranging from 0 (fully flexible) to 1 (completely locked). The coefficient captures the aggregate rigidity arising from technological, institutional, and political lock-in mechanisms operating simultaneously.

ρ = f(Fossil Share, Import Lock, Institutional Entrenchment)

where f(·) represents an unspecified aggregation function whose precise form and component weights require empirical calibration beyond this study's scope. The three arguments capture observable dimensions corresponding to distinct lock-in mechanisms:

Fossil infrastructure share captures technological lock-in through the proportion of primary energy or electricity generation from coal and other fossil fuels. Higher shares indicate greater sunk capital at risk and larger stranded asset exposure from rapid transition, directly reflecting Arthur's increasing returns mechanisms.

Import dependency structure measures coordination lock-in through reliance on imported fossil fuels, particularly where long-term contracts, dedicated pipeline infrastructure, or strategic relationships create switching costs. This dimension captures how energy systems coordinate around incumbent supply arrangements, making unilateral departure costly.

Political-institutional entrenchment assesses distributional lock-in through how deeply carbon-intensive arrangements embed in governance structures, including fiscal dependence on fossil fuel revenues, employment concentration in extractive regions, and regulatory frameworks designed around incumbent technologies. This dimension captures Pierson's insight that policies create defending constituencies.

For Turkey, qualitative assessment across these dimensions yields ρ≈0.65: fossil fuels supply approximately 83% of primary energy (high technological lock-in), natural gas import dependency exceeds 98% through pipeline infrastructure with limited diversification options (high coordination lock-in), and coal mining regions exercise significant influence over energy policy through both employment stakes and political representation (high distributional lock-in) [11]. This composite assessment indicates severe structural constraints on transformation speed regardless of policy ambition.

For China, we estimate ρ≈0.50, reflecting a different lock-in profile. While coal remains significant in energy supply (moderate technological lock-in), domestic production reduces import dependency (lower coordination lock-in). The binding constraint involves institutional complementarities in industrial governance rather than energy infrastructure per se. Park-level carbon accounting integrates with regional development evaluation, state enterprise management, and environmental regulatory systems in ways that resist isolated modification (high institutional lock-in) [12].

For India, we estimate ρ≈0.35, the lowest among our cases. Coal dependence is substantial but declining, domestic production dominates imports, and the PAT scheme's intensity-based approach has created institutional foundations adaptable to carbon-specific applications. Political lock-in exists but operates less uniformly given India's federal structure and diverse regional energy profiles [13].

We emphasize that ρ values in this study represent informed qualitative judgments rather than outputs of a validated quantitative model. Future research should develop rigorous operationalization through cross-national empirical calibration. The framework's value lies in distinguishing structural constraint from policy choice, enabling analysis of why countries with similar policy ambitions achieve different outcomes.

2.4 Trade Exposure and Bargaining Leverage

Trade exposure intensity shapes strategic options through asymmetric bargaining power. Countries sending large export shares to EU markets possess limited leverage in bilateral negotiations. They cannot credibly threaten market access retaliation or rapid trade diversification. This exposure compels accommodation regardless of domestic preference, narrowing the feasible strategy set toward alignment.

Countries with lower EU exposure and larger domestic markets retain strategic space. They can absorb near-term export losses while pursuing diplomatic contestation or alternative market development. Their threat to restrict EU market access carries more weight given European commercial interests in their domestic consumption. This leverage expands feasible strategies to include resistance and negotiation.

The interaction between path dependency and trade exposure generates distinct strategic imperatives. High ρ combined with high trade exposure creates the most constrained position: rapid transformation is structurally difficult, yet market access imperatives demand compliance. Low ρ with low exposure offers maximum flexibility: adaptation is feasible if chosen, but alternatives exist if preferred. Intermediate combinations produce the most interesting strategic calculations, where countries must weigh partial accommodation against partial resistance.

2.5 Three Strategic Archetypes

From this framework emerge three coherent strategic archetypes representing distinct resolutions of the trilemma.

Defensive adaptation prioritizes preserving domestic institutional arrangements while creating compliance interfaces for international engagement. Countries pursuing this strategy maintain core carbon governance frameworks serving domestic policy objectives, then construct additional layers specifically designed to satisfy external requirements. The approach accepts increased complexity and coordination costs in exchange for avoiding wholesale institutional replacement. It proves feasible when countries possess sufficient technical capacity to operate parallel systems and when domestic institutional arrangements serve important functions beyond carbon accounting.

Dependent integration prioritizes market access through comprehensive regulatory alignment with external standards. Countries pursuing this strategy essentially import carbon governance frameworks from regulatory origin jurisdictions, accepting that domestic policy autonomy diminishes accordingly. The approach minimizes compliance friction and regulatory uncertainty but may impose substantial adjustment costs when domestic conditions differ from those assumed in imported frameworks. It proves necessary when trade exposure is extreme and becomes attractive when domestic carbon governance capacity is limited, making external frameworks a source of institutional resources rather than merely constraints.

Negotiated autonomy prioritizes domestic policy autonomy while actively contesting external regulatory frameworks through diplomatic and legal channels. Countries pursuing this strategy build domestic carbon governance systems reflecting national priorities and development imperatives, then challenge the legitimacy or application of external measures that discount these domestic efforts. The approach accepts near-term compliance costs and market access friction in exchange for preserving policy space and potentially reshaping international rules. It proves feasible when countries possess sufficient market size and alternative partnerships to absorb short-term losses, and when they can mobilize broader coalitions around shared concerns.

2.6 Testable Propositions

The theoretical framework generates specific propositions amenable to empirical testing. We articulate these propositions to clarify the framework's predictive content and invite falsification attempts.

Proposition 1: Path Dependency and Strategic Conservatism. Countries with higher path dependency coefficients (ρ) will adopt less transformative CBAM response strategies, holding trade exposure constant. Specifically, high-ρ countries will favor dependent integration (accepting external frameworks) over defensive adaptation (building parallel systems) or negotiated autonomy (contesting external frameworks), because the coordination costs of parallel system construction exceed the autonomy costs of regulatory import when domestic systems resist modification.

Observable implications: Among countries with similar EU trade exposure, those with higher fossil fuel shares, greater import dependency, and deeper political-institutional entrenchment should exhibit faster and more comprehensive adoption of EU-compatible carbon pricing frameworks.

Proposition 2: Trade Exposure and Convergence Speed. Countries with higher trade exposure to EU markets will converge toward EU carbon accounting standards more rapidly, holding path dependency constant. The commercial stakes of market access create urgency that overcomes domestic resistance, accelerating institutional change that lower-exposure countries can defer.

Observable implications: Among countries with similar ρ values, those with higher EU export shares should exhibit earlier carbon pricing adoption, faster verification body accreditation, and more complete methodological alignment with EU MRR requirements.

Proposition 3: Interaction Effect on Archetype Selection. The ρ-exposure interaction determines archetype selection through a specific logic: high exposure compresses the time horizon for strategic response, while high ρ limits the transformation achievable within that horizon. The interaction produces archetype selection as follows:

- High ρ × High exposure → Dependent integration (no time for parallel systems, no capacity for transformation)

- Moderate ρ × Moderate exposure → Defensive adaptation (sufficient time and capacity for parallel systems)

- Low ρ × Low exposure → Negotiated autonomy (capacity for domestic alternatives, leverage for contestation)

Observable implications: Countries should cluster in the predicted cells of the archetype selection matrix (Table 1). Deviations from predicted positions should correlate with measurement error in ρ or exposure, exogenous shocks disrupting lock-in mechanisms, or strategic miscalculation by policymakers.

These propositions remain subject to refinement as empirical evidence accumulates. The framework's value lies not in claiming certainty but in generating specific, falsifiable predictions that structure ongoing research.

3. China: Defensive Adaptation Through Parallel System Construction

3.1 The Political Logic of Institutional Separation

China's response to CBAM reflects a broader governance philosophy emphasizing domestic institutional autonomy while managing international interdependence through carefully designed interface mechanisms. Rather than replacing established carbon accounting frameworks with EU-compatible alternatives, Chinese policy constructs additional layers that translate between domestic and international requirements. This defensive adaptation strategy accepts complexity costs to preserve core arrangements serving multiple domestic functions beyond CBAM compliance.

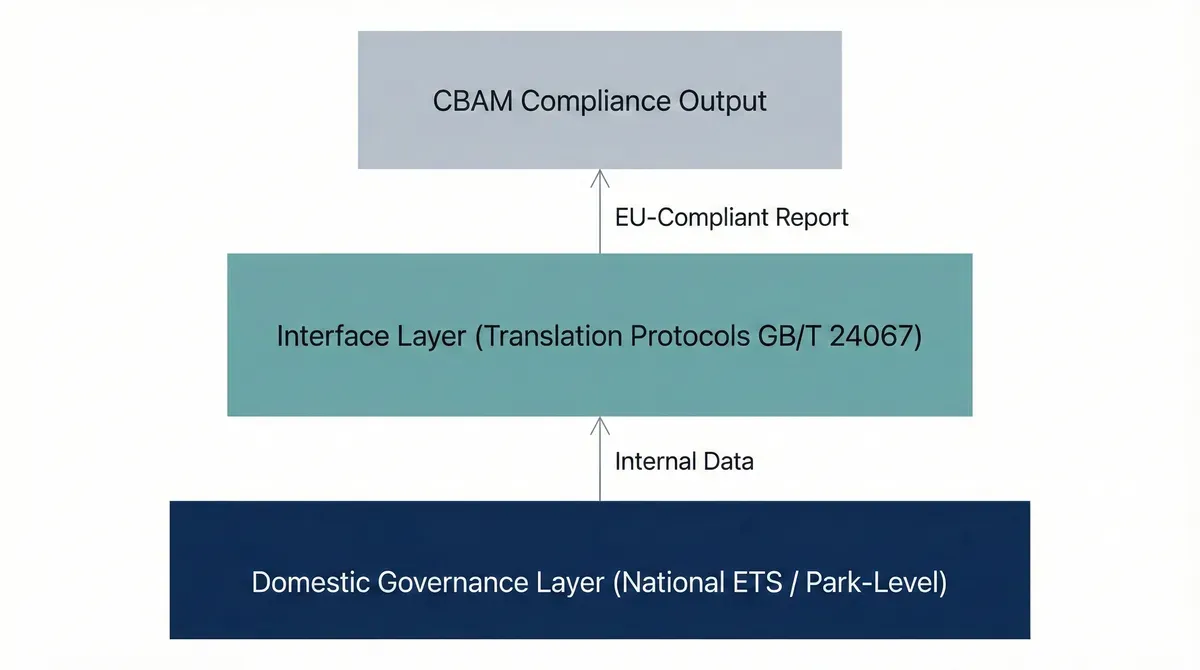

Understanding this choice requires recognizing that China's carbon governance architecture evolved to serve specific domestic objectives. The national Emissions Trading System, launched in 2021 covering power generation and expanding to additional sectors, allocates permits at enterprise and facility levels to support industrial policy goals including regional development balancing and state-owned enterprise management [14]. Park-level industrial organization, where enterprises cluster in designated zones sharing infrastructure and services, reflects decades of economic development strategy emphasizing agglomeration economies [15]. Carbon accounting frameworks that measure emissions at park or enterprise levels align with these governance logics.

CBAM demands something different: product-level carbon intensity data enabling EU importers to calculate certificates required for specific goods. This granularity mismatch means that even sophisticated monitoring systems generating accurate facility-level data cannot directly produce CBAM-compliant declarations. A steel mill may know precisely its annual emissions. Allocating those emissions to specific product grades shipped to specific customers requires additional accounting infrastructure that existing systems do not provide.

The defensive adaptation response constructs this additional infrastructure as an interface layer rather than a replacement system. In June 2024, Chinese authorities released GB/T 24067-2024 establishing product carbon footprint calculation guidelines [16]. This standard creates translation protocols enabling enterprises to generate product-level declarations from underlying facility-level data. Provincial pilots in Shanghai and Guangdong test implementation pathways, allowing enterprises to maintain existing systems for domestic purposes while producing parallel outputs for export documentation [17].

3.2 Three-Layer Defense Architecture

China's approach manifests as a three-layer defense architecture, each layer serving distinct functions while collectively managing the domestic-international interface.

The foundation layer preserves existing carbon governance arrangements. National ETS continues operating with enterprise-level allocation and compliance. Provincial carbon markets maintain their established frameworks. Industrial park management retains carbon accounting at cluster levels. These arrangements serve ongoing domestic policy objectives including emissions intensity targets under five-year plans, regional competitiveness management, and state-owned enterprise performance evaluation. CBAM compliance requirements do not penetrate this layer, which remains insulated from external regulatory influence.

The interface layer constructs translation mechanisms between domestic and international requirements. Product carbon footprint standards like GB/T 24067-2024 define methodologies for deriving product-level data from facility-level inputs. Verification protocols enable third-party attestation of these calculations. Data management platforms aggregate enterprise submissions into formats compatible with EU reporting templates. This layer handles the technical work of regulatory translation, converting information that exists in one form into information required in another form.

The strategic layer manages diplomatic and commercial positioning around CBAM implementation. Chinese authorities have signaled openness to bilateral discussions with the European Commission on mutual recognition of carbon pricing systems [18]. Industry associations coordinate enterprise responses to minimize competitive disadvantage. Government-backed research develops arguments for recognizing China's existing carbon costs, including provincial carbon markets and energy efficiency regulations, as equivalent measures deserving CBAM credit.

This three-layer architecture accepts substantial coordination complexity. Enterprises must maintain parallel data systems, verification relationships, and reporting procedures. Government agencies must develop and enforce interface standards while managing ongoing domestic systems. The complexity costs prove acceptable because the alternative, wholesale replacement of domestic arrangements with EU-compatible frameworks, would disrupt governance systems serving functions beyond carbon accounting and would concede regulatory sovereignty to external standard-setters.

3.3 Path Dependencies in Park-Level Governance

China's institutional path dependency differs from energy infrastructure lock-in observed elsewhere. Coal remains significant in Chinese energy supply, but the more binding constraint involves industrial organization rather than power generation. Park-level governance creates institutional interdependencies that make accounting unit changes costly even when technical capacity exists.

Industrial parks in China function as integrated governance units. Local governments evaluate park management based on aggregate metrics including output, employment, and environmental performance. Infrastructure investments, including power supply, wastewater treatment, and logistics facilities, serve the park as a whole rather than individual enterprises. Regulatory oversight, including environmental permits and safety inspections, often operates at park level. These arrangements create efficiencies through shared services and coordinated management.

Carbon accounting at park level aligns with this governance structure. Emissions monitoring equipment may serve multiple facilities. Verification procedures audit park-level totals rather than enterprise-specific claims. Allocation methodologies distribute responsibility across park tenants based on negotiated formulas. Shifting to facility-level or product-level accounting requires renegotiating these arrangements, redistributing costs and responsibilities among parties with established expectations.

The path dependency coefficient for Chinese industrial governance, while difficult to quantify precisely, reflects these institutional interdependencies. Technical capacity for granular monitoring exists; Chinese CEMS deployment rates approach European levels in major industrial sectors [19]. The constraint lies in institutional arrangements that channel monitoring data into park-level aggregations rather than product-level intensities. Changing these arrangements requires coordinated action across multiple government agencies, enterprise managers, and park authorities, a process measured in years rather than months.

3.4 Strategic Implications of Defensive Adaptation

China's defensive adaptation strategy carries significant implications for global carbon governance evolution. If successful, it demonstrates that major economies can satisfy CBAM requirements without fundamentally altering domestic carbon governance architectures. This outcome might encourage other countries to pursue similar parallel system approaches, potentially fragmenting international carbon accounting into incompatible regional frameworks connected only through interface mechanisms.

The strategy also reveals limits of border carbon adjustments as convergence instruments. CBAM proponents often assume that compliance pressure will drive trading partners toward EU-style carbon pricing and accounting frameworks [20]. China's response suggests an alternative trajectory: building just enough compatibility to maintain market access while preserving fundamentally different underlying systems. If this approach succeeds, CBAM achieves its narrow objective of preventing carbon leakage without its broader aspiration of catalyzing global carbon pricing convergence.

For Chinese enterprises, defensive adaptation creates both opportunities and burdens. Companies with resources to navigate parallel systems can potentially demonstrate lower carbon intensity than EU default values, gaining competitive advantage. Smaller exporters lacking capacity for sophisticated carbon management may find themselves priced out of European markets, accelerating industrial consolidation. The strategy's domestic distributional consequences remain uncertain and will shape political sustainability over time.

4. Turkey: Dependent Integration and the Path Dependency Trap

4.1 The Compulsion of Trade Exposure

Turkey's response to CBAM follows a starkly different logic than China's defensive adaptation. Where China constructs parallel systems preserving institutional autonomy, Turkey pursues comprehensive regulatory alignment that essentially imports EU carbon governance frameworks wholesale. This dependent integration strategy reflects Turkey's extreme trade exposure and limited bargaining leverage, conditions that narrow feasible options to accommodation regardless of domestic preference.

The structural position driving this choice emerges clearly from trade statistics. Approximately 41% of Turkish exports flow to EU markets, with steel and cement representing particularly significant sectors [21]. EU imports of iron and steel from Turkey reached €3.5 billion in 2024, making Turkey the EU's third-largest steel supplier; Turkish cement exports to the EU totaled approximately €0.5 billion, representing over 35% of EU cement imports by volume [22]. CBAM's potential to add substantial costs to these exports, potentially exceeding profit margins for high-carbon products, creates existential stakes for major industrial sectors.

This trade dependence eliminates strategic alternatives available to less exposed economies. Turkey cannot credibly threaten market access retaliation; EU exports to Turkey are proportionally much smaller, creating asymmetric vulnerability. Diversifying export markets requires years of relationship building and faces competition from established suppliers. Absorbing CBAM costs while contesting mechanism legitimacy proves financially unsustainable for trade volumes at stake. The structural position compels alignment, transforming what might otherwise be a strategic choice into a structural necessity.

4.2 Comprehensive Institutional Mirroring

Turkey's response manifests as comprehensive institutional mirroring, replicating EU carbon governance frameworks in detail rather than merely creating interface mechanisms. The centerpiece is Turkey's Climate Law enacted in July 2025, establishing the legal foundation for a national Emissions Trading System designed for maximum EU compatibility [23].

The legislation's architecture reveals the depth of alignment. Coverage thresholds mirror EU ETS rules, capturing installations exceeding specified emission levels across power generation, industrial production, and aviation. Allocation methodology follows EU approaches, combining free allocation based on benchmarks with auctioning shares that increase over time. Compliance mechanisms including banking, borrowing, and penalty structures track EU precedents [24]. The Istanbul Energy Exchange receives designation as the trading platform, paralleling how European energy exchanges operate carbon markets [25].

Even institutional governance reflects EU templates. A Carbon Market Board modeled on European financial regulators exercises oversight authority. Monitoring, reporting, and verification requirements align with EU MRR standards. Accreditation procedures for verification bodies follow EU-recognized certification frameworks. The intent is not merely policy similarity but regulatory interoperability, positioning Turkey's system for potential linking with EU ETS and automatic recognition under CBAM provisions for equivalent carbon pricing [26].

This comprehensive approach contrasts with more selective alignment strategies. Turkey could have adopted carbon pricing covering only export-oriented sectors, creating a minimal compliance footprint. Instead, economy-wide coverage mirrors EU scope. Turkey could have maintained distinct monitoring protocols adapted to domestic conditions. Instead, EU MRR adoption creates direct compatibility. The pattern suggests that regulatory convergence serves objectives beyond narrow CBAM compliance, potentially including eventual EU membership aspirations despite their current political dormancy.

4.3 The ρ≈0.65 Constraint: When Policy Outpaces Physical Reality

Despite ambitious institutional alignment, Turkey confronts a severe constraint: energy system path dependencies that resist rapid transformation regardless of policy intent. We estimate Turkey's path dependency coefficient at ρ≈0.65, indicating substantial rigidity that limits how quickly policy reforms translate into emissions reductions.

The calculation reflects multiple lock-in mechanisms operating simultaneously. Coal and lignite generation accounted for 34.5% of Turkish electricity supply in 2024, with much of this capacity representing relatively recent investments [27]. Plants commissioned in the 2010s have decades of remaining technical life. Early retirement would generate stranded asset costs borne by investors, utilities, or government, creating political resistance to aggressive phase-out timelines. This represents technological lock-in through sunk capital with long recovery horizons.

Natural gas provides another 30% of generation, but Turkey imports over 90% of gas supplies, primarily from Russia and Azerbaijan [28]. Reducing gas dependence requires alternative supply arrangements or demand reduction that energy security concerns complicate. Long-term contracts, pipeline infrastructure, and geopolitical relationships create coordination lock-in extending beyond simple fuel substitution economics.

Beyond energy supply, industrial carbon intensity reflects production technologies with long replacement cycles. Turkish steel production relies significantly on blast furnace routes with higher carbon intensity than electric arc alternatives [29]. Cement kilns designed for coal firing cannot easily switch to alternative fuels without substantial capital investment. These industrial path dependencies compound energy system constraints, creating layered rigidity that institutional reforms cannot rapidly overcome.

Turkey's aggressive renewable energy targets, including 50% renewable generation by 2030, represent policy aspirations that path dependency makes difficult to achieve [30]. Wind and solar deployment accelerates but cannot fully offset baseload coal capacity within CBAM-relevant timelines. The gap between regulatory alignment and physical transformation creates a structural trap: Turkey may achieve EU-compatible carbon pricing institutions while actual emissions reductions lag behind, leaving exporters facing CBAM costs despite domestic compliance.

4.4 Strategic Implications of Dependent Integration

Turkey's dependent integration strategy illuminates both the power and limits of border carbon adjustments as governance instruments. On one hand, CBAM has successfully induced comprehensive regulatory alignment from a major trading partner without formal treaty negotiation or explicit conditionality. Turkey adopted EU-compatible carbon pricing not through membership accession requirements but through commercial pressure alone. This represents significant regulatory reach extending EU climate policy influence beyond formal jurisdiction.

On the other hand, Turkish experience reveals that regulatory alignment without corresponding physical transformation may achieve limited environmental outcomes while imposing substantial economic costs. If Turkish industrial carbon intensity remains elevated due to energy system constraints, CBAM functions primarily as a trade barrier rather than an environmental incentive. Turkish exports face cost disadvantages reflecting historical energy investments rather than current production choices. The mechanism penalizes path dependency as much as policy inadequacy.

For Turkish enterprises, dependent integration creates immediate compliance certainty alongside medium-term competitive uncertainty. Companies know which standards to meet and can benchmark against EU peers. Whether they can meet those standards at viable cost given energy system constraints remains unclear. Some sectors, particularly cement with its global industry coordination through GCCA frameworks, have developed carbon accounting capabilities positioning them favorably [31]. Others, including fragmented steel mini-mill operators, lack comparable institutional support and face default value penalties despite EU-compatible domestic regulation.

The political economy of adjustment presents additional challenges. Industrial sectors facing competitive pressure from CBAM costs may mobilize against climate policy, framing it as externally imposed constraint rather than domestically chosen strategy. Regional employment in coal supply chains creates concentrated interests resisting phase-out, even as diffuse benefits from energy transition remain politically underweighted. Turkey's climate policy sustainability depends on managing these distributional conflicts, a governance challenge that institutional mirroring from the EU does not automatically address.

Would Turkey have developed carbon pricing absent CBAM pressure? The counterfactual suggests probably not, or not at comparable speed. Turkey's 2015 Paris Agreement ratification came six years after initial signature, and domestic climate legislation stalled repeatedly through the late 2010s despite EU accession aspirations. The Climate Law's 2025 passage followed CBAM's 2023 transitional phase announcement by less than two years. Pre-CBAM climate policy discourse in Turkey centered on renewable energy expansion for energy security rather than carbon pricing for emissions reduction. The carbon market emerged specifically as a CBAM interface mechanism, not as an indigenous policy choice subsequently aligned with European frameworks. This sequencing supports interpreting Turkish carbon governance as externally induced rather than domestically driven, dependent integration in its purest form.

5. India: Negotiated Autonomy and Strategic Contestation

5.1 The Structural Basis for Resistance

India's response to CBAM diverges fundamentally from both Chinese defensive adaptation and Turkish dependent integration. Rather than constructing parallel systems or pursuing comprehensive alignment, India combines domestic institution-building with active contestation of CBAM's legitimacy. This negotiated autonomy strategy reflects India's structural position: sufficient scale and trade diversification to absorb near-term costs, combined with self-conception as a Global South leader capable of mobilizing broader coalitions against perceived Northern regulatory overreach.

The structural basis emerges from comparative trade exposure. India's exports to the EU represent approximately 13% of total exports, substantially below Turkey's 41% [32]. While significant in absolute terms, this exposure does not create existential dependence. India's large domestic market, projected GDP growth exceeding 7% annually, and developing trade relationships with alternative partners in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East provide strategic space unavailable to more EU-dependent economies [33].

India's scale amplifies bargaining leverage. As the world's second-largest steel producer and a major aluminum and cement manufacturer, Indian supply disruptions would meaningfully affect global commodity markets. European industries relying on Indian inputs possess commercial interests in maintaining trade flows, creating constituencies within the EU for accommodating Indian concerns. This leverage, while not unlimited, enables negotiating positions that smaller economies cannot sustain.

5.2 The PAT-to-CCTS Institutional Trajectory

India's domestic carbon governance development follows a distinctive trajectory building on existing institutional foundations rather than importing external frameworks. The Perform, Achieve, Trade (PAT) scheme, launched in 2012 under the National Mission for Enhanced Energy Efficiency, established technical and institutional infrastructure now being repurposed for carbon markets [34].

PAT targeted energy intensity rather than carbon emissions directly, setting sector-specific efficiency targets for designated consumers in energy-intensive industries. Enterprises exceeding targets received Energy Saving Certificates (ESCerts) tradeable to underperforming facilities. The scheme's implementation developed significant institutional capacity: baseline-setting methodologies accounting for production variations, monitoring and verification protocols adapted to Indian industrial conditions, and market platforms for certificate transactions.

Crucially, PAT pioneered sophisticated normalization approaches addressing development context challenges. Targets adjusted for capacity utilization, recognizing that plants operating below design capacity face structural efficiency disadvantages. Fuel quality adjustments accounted for variations in coal characteristics across Indian sources. Product mix corrections enabled fair comparison across facilities with different output compositions [35]. This methodological sophistication created templates adaptable to carbon-specific applications.

The transition from PAT to India's Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS), authorized through the 2022 Energy Conservation Amendment Act, leverages this institutional foundation. CCTS coverage extends to nine sectors including steel, cement, aluminum, fertilizer, and thermal power [36]. The baseline-and-credit structure deliberately differs from EU-style cap-and-trade, using intensity targets rather than absolute caps. This design choice reflects both technical path dependency, with existing capacity for intensity-based measurement and allocation, and strategic autonomy, asserting India's right to design climate policy compatible with development imperatives.

The intensity-based approach carries significant implications for CBAM compatibility. EU regulations assume carbon pricing through absolute cap systems, with established methodologies for calculating equivalent prices. Whether intensity-based schemes constitute "equivalent carbon pricing" deserving CBAM recognition remains undefined and contested. India's CCTS design thus combines genuine climate policy functionality with deliberate ambiguity about international equivalence, preserving negotiating leverage.

5.3 Implicit Carbon Pricing as Diplomatic Weapon

Beyond domestic market development, India has pioneered a distinctive diplomatic strategy centered on implicit carbon pricing claims. This approach argues that existing Indian policies, particularly fossil fuel taxation, create carbon costs comparable to explicit carbon pricing and deserving CBAM recognition.

The quantitative basis involves calculating the carbon price equivalent of fuel taxes. Indian excise duties on petroleum products are substantial, often comprising 40-50% of retail prices [37]. Backcasting these tax revenues against fuel carbon content yields implicit carbon prices in the range of $50-80 per ton of CO₂, comparable to or exceeding prices in many explicit trading systems [38]. If recognized, these implicit prices would substantially offset CBAM liabilities for energy-intensive exports.

The argument's diplomatic value extends beyond technical merits. By framing CBAM as potentially discriminatory against alternative forms of carbon pricing, India shifts debate from "India has no carbon price" to "India's carbon pricing takes different forms than Europe's." This reframing creates negotiating space for bilateral agreements, phased implementation timelines, or methodology adjustments that pure compliance pressure would foreclose.

India has pursued this diplomatic track through multiple channels. Formal communications to the European Commission assert that existing Indian policies constitute relevant carbon costs [39]. Statements at UNFCCC proceedings characterize CBAM as inconsistent with common but differentiated responsibilities under the Paris Agreement. Coalition-building with other developing economies facing similar pressures amplifies India's voice beyond its individual weight. The strategy positions India as representing broader Global South interests, potentially influencing not just Indian treatment under CBAM but mechanism design evolution affecting many countries.

5.4 The Green Hydrogen Leapfrog Strategy

Complementing defensive diplomacy, India pursues technological leapfrogging through ambitious green hydrogen development. The National Green Hydrogen Mission, launched in 2023, targets 5 million tons of annual production capacity by 2030, positioning India as a potential global hub for hydrogen production and export [40].

For carbon-intensive exports, hydrogen enables transformation pathways that could fundamentally alter CBAM exposure. Steel production through hydrogen-based direct reduced iron (DRI) achieves near-zero process emissions, potentially making Indian green steel more competitive than conventional production even under stringent carbon pricing. Major producers including JSW Steel and Tata Steel have announced pilot facilities exploring this route [41].

The leapfrogging logic inverts standard development assumptions. Rather than following the conventional path from high-carbon to incrementally lower-carbon production, India targets direct transition to near-zero-carbon technologies, bypassing intermediate stages. If successful, this approach would render CBAM pressures largely irrelevant for transformed industries while creating export opportunities in emerging low-carbon product markets.

The strategy carries substantial risks. Green hydrogen costs remain above fossil alternatives despite rapid decline. Infrastructure for hydrogen production, storage, and industrial application requires massive investment. Technology pathways remain partially unproven at scale. Whether India can achieve hydrogen economics competitive with conventional production within CBAM-relevant timelines remains uncertain [42].

Yet the strategy's option value is significant. By developing hydrogen capabilities in parallel with CBAM contestation and domestic market development, India hedges across multiple scenarios. If diplomatic efforts achieve CBAM accommodation, hydrogen investments position India for emerging low-carbon markets. If CBAM pressure intensifies, hydrogen offers a transformation pathway preserving export competitiveness. If hydrogen economics prove unfavorable, diplomatic gains and domestic carbon markets provide fallback positions. This portfolio approach reflects negotiated autonomy's core logic: maintaining multiple options rather than committing fully to any single pathway.

5.5 Strategic Implications of Negotiated Autonomy

India's negotiated autonomy strategy offers a distinct model for CBAM response, available primarily to countries with sufficient scale and diversification to sustain near-term costs while contesting long-term rules. The strategy's success would reshape global carbon governance by legitimizing alternative carbon pricing forms and constraining unilateral border measures.

If implicit carbon pricing gains recognition, the precedent would extend far beyond India. Many developing countries maintain fossil fuel taxes that could claim equivalent status. CBAM's revenue implications would diminish substantially if such claims prevailed. The mechanism's environmental effectiveness would depend on verification arrangements ensuring that claimed carbon prices actually affect production decisions rather than merely generating fiscal revenue.

Coalition-building aspects of negotiated autonomy may prove more consequential than bilateral outcomes. If India successfully mobilizes Global South opposition to CBAM, pressure could build for mechanism modification through multilateral channels. The WTO dispute system, Paris Agreement negotiations, or new institutional arrangements might constrain unilateral border measures in ways that bilateral negotiations would not achieve. This multilateral dimension distinguishes negotiated autonomy from purely bilateral resistance.

For Indian enterprises, the strategy creates medium-term uncertainty. Unlike Turkish companies facing clear compliance requirements, Indian exporters navigate ambiguous terrain where applicable standards and recognition arrangements remain contested. Some enterprises, particularly those serving EU customers demanding verified carbon footprints, pursue voluntary alignment exceeding domestic requirements [43]. Others await policy resolution before investing in carbon management capabilities. This heterogeneity may prove efficient if different enterprises correctly anticipate different scenarios, or costly if miscalculations strand investments in the wrong direction.

6. Comparative Analysis: Structural Position and Strategic Choice

6.1 The Archetype Selection Matrix

Comparing strategic archetypes across the three cases reveals how structural position shapes response feasibility. We can organize this relationship through an archetype selection matrix relating path dependency (ρ) and trade exposure to strategic options.

Table 1: Archetype Selection Matrix

| High Trade Exposure (>40%) | Moderate Trade Exposure (15-40%) | Low Trade Exposure (<15%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High ρ (>0.6) | Dependent Integration (Turkey: ρ≈0.65, EU exp.=41%) | Constrained Adaptation | Strategic Insulation |

| Moderate ρ (0.4-0.6) | Accelerated Alignment | Defensive Adaptation (China: ρ≈0.50, EU exp.=16%) | Selective Engagement |

| Low ρ (<0.4) | Voluntary Convergence | Opportunistic Positioning | Negotiated Autonomy (India: ρ≈0.35, EU exp.=13%) |

Note: ρ = path dependency coefficient measuring system rigidity across technological, institutional, and political dimensions; Trade Exposure = share of total exports destined for EU markets. Shaded cells indicate case study positions. Cell labels indicate dominant strategic orientation for each structural configuration.

The matrix reveals that archetype selection is not discretionary but structurally constrained. Countries cannot freely choose among strategies; their position in ρ-exposure space determines which strategies remain viable, consistent with Proposition 3.

High trade exposure combined with high path dependency creates the most constrained position, essentially forcing dependent integration. Turkey exemplifies this configuration. With 41% export dependence on EU markets and ρ≈0.65 constraining transformation speed, Turkey lacks viable alternatives to regulatory alignment. Resistance would sacrifice market access that cannot be readily replaced. Defensive adaptation through parallel systems requires institutional flexibility that comprehensive alignment consumes. The structural position leaves dependent integration as the only sustainable path.

Moderate trade exposure combined with moderate path dependency enables defensive adaptation. China exemplifies this configuration. With diversified trade relationships reducing EU dependence and institutional rather than energy infrastructure path dependency, China retains strategic space. Parallel systems require sophistication that China possesses. The costs of operating dual frameworks, while substantial, remain manageable given overall economic scale. Defensive adaptation resolves the trilemma by accepting complexity costs to preserve both market access and institutional autonomy.

Lower trade exposure combined with lower path dependency permits negotiated autonomy. India exemplifies this configuration. With 13% EU export share and sufficient domestic market scale, India can absorb near-term compliance costs while contesting mechanism legitimacy. The PAT-to-CCTS institutional trajectory provides domestic alternatives to EU frameworks. Coalition-building potential amplifies leverage beyond individual weight. Negotiated autonomy accepts market access friction to preserve policy space and potentially reshape international rules.

6.2 Dynamic Considerations and Strategy Evolution

Strategic archetypes are not permanent classifications but reflect current structural positions that may evolve. Several dynamic factors could shift countries between archetypes over time.

Energy transition progress affects path dependency coefficients. As renewable energy deployment accelerates and fossil fuel assets depreciate, ρ values decline, potentially opening new strategic options. Turkey's aggressive renewable targets, if achieved, would reduce energy infrastructure lock-in, possibly enabling more autonomous positioning in future negotiations. Conversely, delayed transitions lock in current constraints.

Trade relationship evolution affects exposure intensity. China's Belt and Road investments cultivate alternative markets that further reduce EU dependence, reinforcing defensive adaptation feasibility. India's developing partnerships with Gulf states, Southeast Asia, and Africa similarly diversify exposure. Turkey's EU Customs Union membership, however, institutionalizes trade dependence in ways that resist diversification.

CBAM implementation experience may reshape the mechanism itself. If significant trading partners adopt defensive adaptation or negotiated autonomy approaches, pressure may build for EU accommodation through broader equivalent measure recognition or extended transition timelines. Conversely, successful dependent integration by countries like Turkey validates the mechanism's effectiveness, potentially encouraging expansion to additional sectors or strengthening of requirements.

6.3 Implications for Global Carbon Governance

The three strategic archetypes carry distinct implications for global carbon governance evolution. Widespread defensive adaptation would fragment international carbon accounting into incompatible regional systems. If major economies maintain domestic frameworks while constructing minimal interface mechanisms for trade compliance, no unified global carbon accounting standard emerges. Data remains siloed in national systems, verification proceeds through bilateral recognition rather than international harmonization, and carbon prices vary substantially across jurisdictions despite nominal CBAM convergence pressure.

Prevalent dependent integration would concentrate regulatory authority in first-mover jurisdictions. If CBAM successfully compels comprehensive alignment from trading partners, the EU effectively exports its carbon governance framework globally through commercial pressure alone. This outcome extends EU regulatory reach without corresponding extension of EU resources, adjustment support, or political accountability to affected populations. The asymmetric burden distribution may generate backlash that ultimately undermines climate cooperation.

Successful negotiated autonomy would reshape multilateral frameworks themselves. If India's coalition-building and diplomatic contestation compel CBAM modifications recognizing alternative carbon pricing forms, the precedent legitimizes developing country voice in climate trade governance. Future mechanisms would emerge through negotiation rather than unilateral imposition. However, this pathway also risks deadlock if positions prove irreconcilable, potentially delaying meaningful carbon pricing expansion.

The most likely trajectory involves all three archetypes coexisting, with different countries selecting strategies matching their structural positions. This heterogeneous landscape complicates but does not preclude progress on global carbon governance. Interface mechanisms can connect different national systems even without full harmonization. Bilateral and plurilateral arrangements can achieve partial coordination among willing participants. The key is recognizing that uniform convergence toward EU frameworks represents one possible outcome among several, not an inevitable destination.

7. Conclusion: Strategic Alignment with Structural Reality

This analysis yields a blunt conclusion: countries do not choose CBAM strategies freely. Trade exposure and path dependency coefficients box them in, channeling them toward archetypal responses regardless of what policymakers might prefer in the abstract.

The theoretical framework developed here advances understanding by specifying the micromechanisms through which structural position constrains choice. Path dependency operates not as a single force but through compounding technological, institutional, and political lock-in, each mechanism reinforcing the others. Countries with high ρ face not merely technical barriers to transformation but interlocking constraints that resist isolated intervention. Trade exposure interacts with path dependency by compressing the time horizon available for strategic response, forcing high-exposure countries into accommodation regardless of transformation capacity.

The three testable propositions, linking ρ to strategic conservatism, exposure to convergence speed, and their interaction to archetype selection, provide a falsifiable framework for ongoing research. As CBAM implementation proceeds and more countries reveal their strategic responses, systematic testing can refine or reject these propositions. The goal is not to claim deterministic certainty but to generate productive hypotheses structuring empirical inquiry.

Developing economy policymakers face a harder truth: copying works for nobody. Turkey's dependent integration succeeds, if it does, because Turkey has no other move. Countries with different trade exposure or path dependency profiles attempting the same strategy may find themselves paying alignment costs without gaining alignment benefits. India's negotiated autonomy requires scale and coalition-building capacity that smaller economies simply lack. The lesson is negative: know your structural position before choosing, because the wrong archetype extracts costs without delivering gains.

European policymakers expecting uniform convergence will be disappointed. CBAM will produce all three responses simultaneously: some partners aligning comprehensively, others constructing Potemkin compliance systems, still others contesting the mechanism through WTO challenges and diplomatic pressure. This heterogeneity is not implementation failure but structural inevitability. Flexibility beats insistence.

Climate governance scholarship has focused heavily on technical compliance and carbon accounting methodology. This focus misses the political economy driving actual state behavior. Countries' strategic calculations involve sovereignty, distributional consequences, and coalition dynamics. Understanding CBAM responses requires integrating international relations, comparative politics, and economic geography perspectives. The purely environmental lens sees only the tip of the iceberg.

The three strategic archetypes identified here, defensive adaptation, dependent integration, and negotiated autonomy, represent initial conceptualization rather than exhaustive typology. Additional archetypes may emerge as more countries confront CBAM compliance decisions. Hybrid strategies combining elements of multiple archetypes may prove sustainable for countries with intermediate structural positions. Empirical research tracking strategy evolution over CBAM's implementation period will refine and extend the framework developed here.

CBAM's ultimate significance for global carbon governance hinges on these responses. Widespread defensive adaptation fragments rather than unifies. Prevalent dependent integration deepens the gap between standard-setters and standard-takers. Successful negotiated autonomy rewrites the rules entirely. The strategic choices examined here determine which future arrives.

References

[1] European Commission. (2024). CBAM Transitional Registry: First Period Analysis. DG TAXUD Internal Report. Brussels.

[2] European Commission. (2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/956 establishing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Official Journal of the European Union, L 130.

[3] European Commission. (2023). Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/1773 on CBAM transitional rules. Official Journal of the European Union, L 228.

[4] Arthur, W. B. (1989). Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events. The Economic Journal, 99(394), 116-131.

[5] Arthur, W. B. (1994). Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

[6] North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[7] Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics. American Political Science Review, 94(2), 251-267.

[8] Fouquet, R. (2016). Path Dependence in Energy Systems and Economic Development. Nature Energy, 1, 16098.

[9] Unruh, G. C. (2000). Understanding Carbon Lock-in. Energy Policy, 28(12), 817-830.

[10] Capoccia, G., & Kelemen, R. D. (2007). The Study of Critical Junctures: Theory, Narrative, and Counterfactuals in Historical Institutionalism. World Politics, 59(3), 341-369.

[11] International Energy Agency. (2024). Turkey Energy Policy Review. Paris: IEA.

[12] Wang, J., & Liu, Y. (2023). Industrial Park Governance and Environmental Policy Implementation in China. Journal of Chinese Governance, 8(2), 234-256.

[13] Bureau of Energy Efficiency. (2024). PAT Scheme: A Decade of Implementation. New Delhi: BEE.

[14] Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. (2024). National Carbon Market Construction Progress Report. Beijing: MEE.

[15] Zeng, D. Z. (2010). Building Engines for Growth and Competitiveness in China: Experience with Special Economic Zones and Industrial Clusters. Washington DC: World Bank.

[16] Standardization Administration of China. (2024). GB/T 24067-2024: Product Carbon Footprint Assessment Guidelines. Beijing: Standards Press of China.

[17] Shanghai Development and Reform Commission. (2024). Implementation Plan for Product Carbon Footprint Pilot Program. Shanghai Municipal Government.

[18] Ministry of Commerce of China. (2024). Statement on China-EU Carbon Market Cooperation Dialogue. Beijing: MOFCOM.

[19] China Electricity Council. (2024). Annual Report on CEMS Deployment in Power Sector. Beijing: CEC.

[20] Mehling, M. A., et al. (2019). Designing Border Carbon Adjustments for Enhanced Climate Action. American Journal of International Law, 113(3), 433-481.

[21] Turkish Statistical Institute. (2024). Foreign Trade Statistics 2023. Ankara: TurkStat.

[22] Eurostat. (2025). EU Trade in Iron and Steel 2024. Luxembourg: European Commission.

[23] Republic of Turkey. (2025). Climate Law No. 7552. Official Gazette, July 2025.

[24] Yılmaz, M., & Demir, E. (2025). Turkey's ETS Design: Balancing EU Compatibility and Domestic Flexibility. Climate Policy, 25(3), 345-362.

[25] Energy Market Regulatory Authority of Turkey. (2025). Carbon Market Establishment Decree. Ankara: EMRA.

[26] European Commission. (2024). EU-Turkey Regulatory Dialogue on Carbon Markets. DG CLIMA Technical Paper.

[27] Turkish Wind Energy Association. (2024). Renewable Energy Statistics 2024. Ankara: TWEA.

[28] Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. (2024). Turkey's Natural Gas Import Dependency: Geopolitical Dimensions. Oxford: OIES.

[29] World Steel Association. (2024). Steel Statistical Yearbook 2024. Brussels: worldsteel.

[30] Republic of Turkey Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. (2024). National Energy Plan 2024-2035. Ankara.

[31] Global Cement and Concrete Association. (2024). Member Company Directory and GNR Participation. London: GCCA.

[32] Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India. (2024). Export Statistics by Destination. New Delhi: MoCI.

[33] International Monetary Fund. (2024). World Economic Outlook: India Chapter. Washington DC: IMF.

[34] Bureau of Energy Efficiency. (2024). PAT Scheme: A Decade of Implementation. New Delhi: BEE.

[35] Bureau of Energy Efficiency. (2024). PAT Normalization Methodology Technical Manual. New Delhi: BEE.

[36] Ministry of Power, Government of India. (2022). Energy Conservation (Amendment) Act, 2022. New Delhi.

[37] Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell. (2024). Fuel Price Structure and Taxation in India. New Delhi: PPAC.

[38] Council on Energy, Environment and Water. (2024). Implicit Carbon Pricing in India: Quantification Study. New Delhi: CEEW.

[39] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. (2024). Communication to European Commission on CBAM Equivalent Measures. New Delhi: MEA.

[40] Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. (2023). National Green Hydrogen Mission. New Delhi: MNRE.

[41] Tata Steel. (2024). Green Steel Initiative: Progress Report. Mumbai: Tata Steel.

[42] NITI Aayog. (2024). Green Hydrogen Roadmap: Investment Requirements. New Delhi: Government of India.

[43] Global Trade Research Initiative. (2024). CBAM Impact Assessment for Indian Steel Exports. New Delhi: GTRI.

Authors

Alex is the founder of the Terawatt Times Institute, developing cognitive-structural frameworks for AI, energy transitions, and societal change. His work examines how emerging technologies reshape political behavior and civilizational stability.

U.S. energy strategist focused on the intersection of clean power, AI grid forecasting, and market economics. Ethan K. Marlow analyzes infrastructure stress points and the race toward 2050 decarbonization scenarios at the Terawatt Times Institute.

Maya is a communications strategist bridging technical modeling and public policy. She synthesizes research on grid modernization and decarbonization, ensuring data-driven insights reach legislators and industry stakeholders.