Abstract

Carbon accounting quality varies dramatically across industries and countries, yet existing frameworks struggle to explain why facilities with identical monitoring equipment produce vastly different compliance outcomes under the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. This study develops a Technology-Maturity (TM) framework decomposing carbon accounting capability into two distinct dimensions. The Technology dimension (T) captures hardware and data infrastructure through monitoring equipment coverage, data digitalization level, and methodology precision. The Maturity dimension (M) assesses institutional infrastructure through standardization depth, verification ecosystem density, and historical data continuity. Unlike the IPCC Tier system's focus on scientific precision or the UNFCCC MRV framework's emphasis on political transparency, the TM framework diagnoses the specific capability configurations determining commercial compliance outcomes. Applying this framework across power, steel, cement, and aluminum sectors in Germany, China, Turkey, and India reveals that technical capability and institutional maturity follow independent developmental trajectories. China's power sector achieves high T scores approaching Germany's benchmark, yet faces constrained M due to accounting unit misalignment between facility-level domestic systems and product-level CBAM requirements. Turkey's cement industry demonstrates the reverse pattern, with international standard adoption outpacing monitoring infrastructure deployment. These T-M mismatches generate distinct compliance challenges requiring targeted interventions. The framework further identifies a three-layer digital architecture underlying carbon data flows: physical monitoring (Layer 1), data transmission and security (Layer 2), and verification ecosystems (Layer 3). Germany's public digital infrastructure investments effectively socialize Layer 2 costs, enabling small enterprise participation that fragmented private systems cannot achieve. For practitioners, we provide a diagnostic matrix matching TM deficit patterns to specific policy remedies, demonstrating that effective carbon accounting development requires coordinated advancement across hardware, standards, and verification rather than isolated investments in any single component.

1. Introduction

In the control room of a major Chinese coal-fired power plant, banks of monitors display real-time emissions data streaming from Continuous Emissions Monitoring Systems installed across the facility. The technology represents state-of-the-art capability, with measurement uncertainty below 1.5% for carbon dioxide concentrations. Data flows automatically into the plant's distributed control system, enabling combustion optimization that has reduced emission intensity by 12% over five years. By any reasonable technical metric, this facility operates world-class monitoring infrastructure [1].

Yet when plant managers attempted to complete CBAM transitional declarations for electricity exported to a European industrial customer, they confronted an unexpected obstacle. Their sophisticated monitoring systems produced facility-level annual totals perfectly suited for domestic Emissions Trading System compliance. CBAM required something different: carbon intensity per megawatt-hour of specific electricity deliveries, calculated using methodologies aligned with EU Monitoring and Reporting Regulation standards. The monitoring hardware could theoretically generate such data. The institutional infrastructure to process, verify, and certify product-level declarations did not exist [2].

This vignette captures a puzzle that animates carbon accounting globally. Technical capability and compliance capacity correlate imperfectly. Facilities with advanced equipment sometimes struggle to produce acceptable documentation, while operations with simpler monitoring achieve smooth regulatory approval. Understanding this disconnect requires moving beyond unidimensional assessments of carbon accounting "capacity" toward frameworks that distinguish technical infrastructure from institutional maturity.

The European Union's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism intensifies these questions by creating powerful economic incentives for granular, verified emissions data. Beginning with transitional reporting in October 2023 and moving toward full certificate requirements in 2026, CBAM transforms carbon data from environmental reporting into trade prerequisites [3]. Importers who cannot demonstrate facility-specific emissions through EU-accepted verification face default values deliberately set to penalize incomplete information. For major exporting nations, the ability to generate credible carbon data directly determines market access and competitive positioning.

Existing literature documents carbon pricing policies across jurisdictions and examines CBAM's trade implications, but largely treats carbon accounting capability as an undifferentiated construct [4][5]. This approach obscures critical distinctions. A country might possess extensive monitoring equipment while lacking verification protocols to certify the resulting data. Another might have sophisticated standards and verification bodies but limited physical infrastructure generating source data. These configurations produce different compliance challenges demanding different solutions.

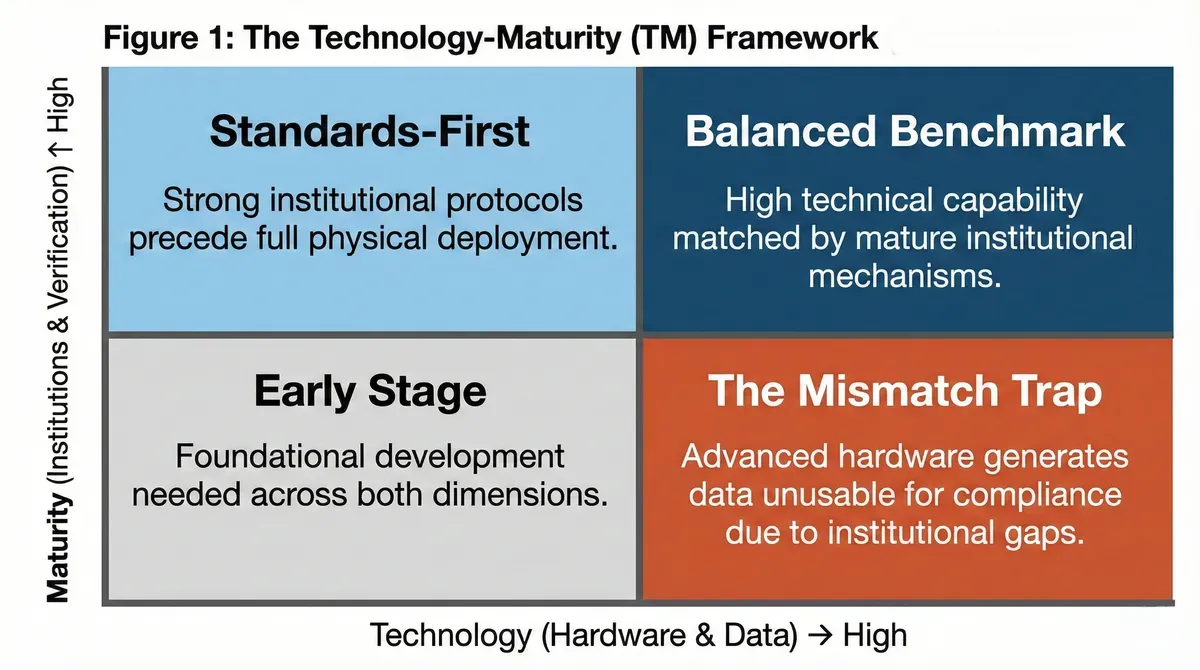

This study develops a Technology-Maturity (TM) framework that decomposes carbon accounting capability into distinct dimensions, enabling precise diagnosis of system strengths and gaps. The Technology dimension assesses hardware and data infrastructure across monitoring coverage, digitalization depth, and methodology precision. The Maturity dimension evaluates institutional infrastructure spanning standardization, verification ecosystems, and data continuity. Together, these dimensions map the architecture of carbon accounting systems in ways that unidimensional indices cannot capture.

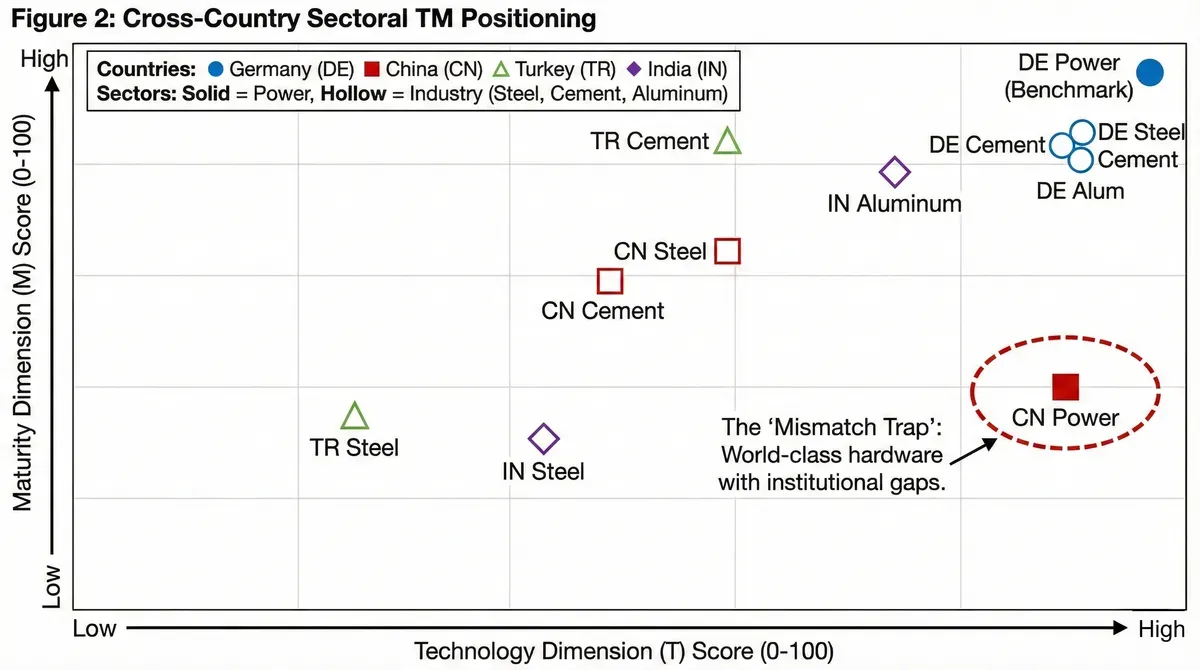

We apply this framework across four countries representing different positions in global carbon governance: Germany as the high-maturity benchmark within the EU system, China as the world's largest emitter with rapidly developing carbon markets, Turkey as an EU Customs Union member facing acute CBAM exposure, and India as a major emerging economy pursuing distinctive climate policy pathways. Within each country, we examine power generation, steel, cement, and aluminum sectors, revealing significant within-country variation that national-level analyses obscure.

The contribution is threefold. Conceptually, we establish that Technology and Maturity represent independent dimensions following distinct developmental logics, a finding that challenges assumptions embedded in existing carbon accounting frameworks. Countries can be high-T/low-M, low-T/high-M, or various intermediate combinations, each configuration generating characteristic compliance patterns. Empirically, we provide detailed sectoral assessments drawing on regulatory documents, industry data, and facility-level case studies spanning 2020-2025. For practitioners, we develop a diagnostic matrix linking TM profiles to targeted interventions, moving beyond generic capacity-building recommendations toward precise remediation strategies.

2. The Technology-Maturity Framework

2.1 Conceptual Foundations: Why Two Dimensions?

Carbon accounting systems convert physical emissions into verified data suitable for regulatory compliance, market transactions, and stakeholder communication. This conversion process involves multiple stages, from initial measurement through data processing to final certification, each stage requiring distinct capabilities. Conflating these capabilities into single indices obscures the specific bottlenecks constraining system performance.

Consider an analogy to healthcare systems. A hospital might possess cutting-edge diagnostic equipment yet struggle with patient outcomes due to inadequate medical training standards or fragmented health records. Alternatively, a facility with modest equipment but excellent protocols and experienced staff might achieve superior results. Evaluating healthcare "capacity" as a single number would miss these crucial distinctions. Carbon accounting exhibits similar multidimensionality.

The Technology dimension captures the physical and digital infrastructure generating raw emissions data. This includes monitoring equipment installed at emission sources, data management systems aggregating and processing measurements, and methodological approaches determining how physical quantities translate into reported emissions. Technology improvements typically require capital investment, technical expertise for installation and maintenance, and organizational capacity to operate sophisticated systems.

The Maturity dimension captures the institutional infrastructure validating and certifying emissions data. This includes standards defining acceptable methodologies and reporting formats, verification bodies with expertise to audit emissions claims, and accumulated historical data enabling trend analysis and baseline comparisons. Maturity improvements typically require regulatory development, professional ecosystem cultivation, and sustained operation generating institutional learning.

These dimensions can develop independently. A country might import monitoring equipment rapidly, achieving high Technology scores within years, while Maturity accumulates gradually through regulatory refinement and verifier experience building. Conversely, a country might adopt international standards and train verification professionals before deploying physical monitoring infrastructure, producing high Maturity with lower Technology. The resulting T-M combinations generate distinct system characteristics.

2.2 Technology Dimension: Hardware and Data Infrastructure

The Technology dimension comprises three components capturing different aspects of physical and digital infrastructure.

T1 measures monitoring equipment coverage, specifically the proportion of emission sources subject to continuous or high-frequency measurement rather than estimation from activity data. For combustion sources, coverage typically means Continuous Emissions Monitoring Systems measuring stack gas flow rates and concentrations. For process emissions like cement calcination or aluminum smelting, coverage involves dedicated sensors tracking relevant parameters. Higher T1 scores indicate more direct measurement and less reliance on emission factors applied to input quantities.

T2 measures data digitalization level, assessing how monitoring data flows through organizational systems and across supply chains. Basic digitalization involves electronic record-keeping replacing paper logs. Intermediate digitalization integrates emissions data with operational systems like Manufacturing Execution Systems or Enterprise Resource Planning platforms. Advanced digitalization enables supply chain data sharing, potentially through blockchain-based verification or cloud platforms aggregating multi-facility data with appropriate access controls.

T3 measures methodology precision, specifically the degree to which reported emissions reflect facility-specific measurements rather than generic emission factors. The IPCC framework distinguishes three tiers: Tier 1 uses global or regional default emission factors, Tier 2 applies country-specific factors, and Tier 3 employs facility-specific measurements or detailed mass balance calculations [6]. Higher T3 scores indicate greater Tier 3 adoption and correspondingly lower uncertainty in reported emissions.

2.3 Maturity Dimension: Institutional Infrastructure

The Maturity dimension similarly comprises three components capturing institutional rather than technical infrastructure.

M1 measures standardization depth, assessing how thoroughly carbon accounting methodologies are codified in mandatory or widely-adopted standards. This includes both the existence of standards and their practical implementation. A country might have comprehensive standards on paper that facilities routinely ignore, or might have limited formal standards supplemented by strong industry norms achieving equivalent standardization.

M2 measures verification ecosystem density, specifically the availability and capability of third-party auditors qualified to certify emissions claims. This involves both quantitative aspects (sufficient verifiers to serve demand without bottlenecks) and qualitative aspects (verifier expertise matching the technical complexity of audited facilities). International accreditation under ISO 14065 provides one marker of verifier quality, though effective verification also requires sector-specific expertise that general accreditation may not capture.

M3 measures historical data continuity, assessing the availability of verified emissions data over time. Regulatory compliance, benchmark setting, and trend analysis all depend on consistent historical records. Longer time series enable more robust baseline construction and performance evaluation. However, quality matters alongside quantity; a decade of unverified estimates provides less value than five years of audited data.

2.4 Methodological Note on Scoring

The TM framework yields assessments along both dimensions, enabling placement in a two-dimensional space revealing system configuration. We characterize sectors as exhibiting "high," "moderate," or "low" scores on each dimension, with approximate numerical ranges provided for comparative purposes. These numerical indications should be understood as qualitative assessments based on observable indicators rather than outputs of validated quantitative models.

Specifically, T scores reflect observable indicators including CEMS coverage rates (where documented), digitalization platform adoption, and methodology tier distribution. M scores reflect verification body counts, standard adoption rates, and historical data availability. The functional relationships aggregating these indicators into composite scores remain subjects for empirical calibration beyond this study's scope. We express this as:

T = f(Monitoring Coverage, Digitalization, Methodology Precision) M = g(Verification Capacity, Data Infrastructure, Institutional Alignment)

where f(·) and g(·) represent unspecified aggregation functions. Future research should develop validated operationalizations enabling cross-national comparison with greater precision.

This methodological humility notwithstanding, the framework's diagnostic value lies in identifying the pattern of T-M relationships rather than precise absolute scores. A sector exhibiting high T with constrained M faces fundamentally different challenges than one with low T and high M, regardless of exact numerical values.

3. Theoretical Context: TM Framework and Existing Carbon Accounting Standards

3.1 The IPCC Tier System: Precision Without Verification

The IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (2006 Guidelines, refined in 2019) provide the methodological foundation for most national carbon accounting [7]. The Tier system embedded within these guidelines offers escalating precision levels: Tier 1 applies global default emission factors to aggregate activity data; Tier 2 employs country-specific factors with more granular activity disaggregation; Tier 3 uses facility-level measurements or complex process models achieving lowest uncertainty.

The IPCC system's core concern is scientific accuracy. It assumes that methodological sophistication translates directly into data quality, with higher tiers producing more accurate national inventories. This assumption holds for scientific purposes but breaks down under CBAM's commercial logic. A facility might achieve Tier 3 precision through advanced monitoring while lacking any mechanism to verify that precision to external parties. The IPCC framework includes quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) recommendations but prescribes no independent verification architecture. As Marlowe and Clarke observe in their systematic review of carbon accounting research, existing frameworks "universally lack consistency, reliability, and comparability" precisely because verification mechanisms remain underdeveloped [8].

The IPCC's unit of analysis compounds this limitation. National inventories aggregate emissions by source category (energy, industrial processes, agriculture) following territorial principles. CBAM requires product-level accounting following supply chain principles. The translation between these paradigms involves boundary definitions, allocation rules, and temporal matching that IPCC guidance does not address. A country achieving Tier 3 national inventory quality has not necessarily developed the infrastructure for Tier 3 product footprints.

3.2 The UNFCCC MRV Framework: Process Without Depth

The UNFCCC's Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) framework, strengthened under the Paris Agreement's Enhanced Transparency Framework (Article 13), establishes international expectations for climate data disclosure [9]. MRV emphasizes procedural compliance: were reports submitted on time, in correct formats, following prescribed templates? The verification component involves Technical Expert Review (TER), a non-adversarial peer assessment focused on capacity building rather than error detection.

MRV serves political functions admirably. It builds international trust through transparency, identifies capacity gaps warranting support, and creates accountability for nationally determined contributions. These functions differ fundamentally from CBAM's requirements. CBAM verification resembles financial auditing more than diplomatic review. Errors translate into monetary penalties. Verification bodies assume legal liability for certified claims. The stakes transform verification from collegial assessment into adversarial assurance.

Research on MRV implementation in developing countries reveals a pattern directly relevant to TM analysis. Teng and Zhang, examining China's Clean Development Mechanism experience, found that project-level technical capacity developed substantially while systemic institutional capacity lagged [10]. Facilities learned to generate compliant project documentation without building broader verification ecosystems. This pattern, high T with constrained M, emerged from MRV's project focus and persists as countries confront CBAM's systemic requirements.

3.3 TM Framework's Distinctive Contribution

The TM framework advances carbon accounting theory by explicitly decoupling dimensions that existing frameworks conflate. IPCC assumes precision enables trust; MRV assumes process enables verification. Both embed linear development models: invest in monitoring, achieve Tier 3, and compliance follows. CBAM experience reveals this linearity as illusory.

The framework's core insight is that technology capability and institutional maturity can develop asynchronously, producing configurations that neither IPCC nor MRV anticipates. Table 1 summarizes the comparative positioning.

Table 1: Comparative Framework Analysis

| Dimension | IPCC Tier System | UNFCCC MRV/ETF | TM Framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core concern | Precision and accuracy | Transparency and process | Capability configuration |

| Analysis unit | National inventory categories | National commitments | Facility/product in national context |

| Primary function | Guide inventory methodology | Ensure commitment fulfillment | Diagnose compliance gaps |

| Verification logic | QA/QC (technical consistency) | Expert review (non-punitive) | Third-party audit (legal/financial stakes) |

| Treatment of heterogeneity | Encourages higher Tiers for key sources | Flexibility provisions | Identifies T-M mismatches |

| Implicit assumption | Higher precision = better quality | Process compliance = transparency achieved | Hardware ≠ trust; requires matched development |

| Limitation | Lacks verification architecture | Macro-level; disconnected from commercial reality | Requires empirical calibration |

The TM framework fills a theoretical gap exposed by CBAM: why do countries with world-class monitoring infrastructure struggle to demonstrate compliance? The answer lies in decoupling. China's power sector exemplifies high-T/low-M configuration, with 96-98% CEMS coverage producing data that institutional frameworks cannot validate for CBAM purposes [11]. The monitoring hardware works; the trust architecture does not. This pattern, invisible to frameworks assuming precision enables compliance, becomes legible through TM analysis.

Unruh's concept of carbon lock-in, originally applied to technological systems, extends usefully to institutional infrastructure [12]. Just as energy systems exhibit path dependence through accumulated capital and learned practices, carbon accounting systems embed institutional arrangements resistant to change. China built facility-level systems serving domestic governance objectives. Reconstructing these for product-level international compliance requires more than technical adjustment; it demands institutional reconfiguration against embedded interests and accumulated practice.

4. The High-Maturity Benchmark: Germany's Carbon Accounting Architecture

4.1 Power Sector: Where Tier 3 Became Standard Practice

Germany provides the appropriate benchmark for TM assessment, representing mature carbon accounting infrastructure developed over two decades of EU ETS participation. German industrial facilities, particularly in power generation, routinely achieve Tier 3 methodological standards that remain aspirational elsewhere. Understanding how Germany reached this position illuminates the infrastructure requirements for comparable achievement.

The German power sector exhibits high T and high M in our framework, reflecting near-complete development across all components. On T1 monitoring coverage, all combustion installations above 10 MW thermal input operate CEMS meeting EN 14181 quality assurance standards [13]. This coverage extends beyond regulatory minimums. While EU requirements mandate CEMS only for largest facilities, German practice applies equivalent monitoring to medium-scale installations as well. The Federal Network Agency's Core Energy Market Data Register (MaStR) provides complete visibility into generation assets, eliminating blind spots that complicate carbon accounting elsewhere [14].

The T2 digitalization score reflects sophisticated data infrastructure extending beyond individual facilities. Smart meter gateways certified by the Federal Office for Information Security provide secure data transmission channels connecting distributed generation, consumption, and storage assets [15]. The Redispatch 2.0 framework requires real-time data uploads from all generation units above 100 kW, creating information flows supporting both grid management and emissions tracking [16]. This public digital infrastructure means that even small facilities connect to centralized data systems rather than operating as information islands.

T3 methodology precision reaches its apex in German practice. Coal-fired plants conduct batch-specific sampling of fuel carbon content, with laboratory analysis determining emission factors for each delivery rather than relying on annual averages. Natural gas facilities employ online gas chromatography continuously analyzing fuel composition [17]. The resulting emission calculations achieve uncertainty levels below 1.5% for carbon dioxide, meeting the most stringent requirements under EU Monitoring and Reporting Regulation.

4.2 Institutional Infrastructure: Verification Depth and Data Continuity

Germany's M dimension scores similarly high, reflecting institutional development paralleling technical infrastructure. On M1 standardization, German facilities operate within the EU ETS Monitoring and Reporting Regulation framework, itself one of the world's most detailed carbon accounting standards. Beyond EU requirements, German implementation frequently exceeds minimum thresholds. Regulatory guidance from the German Emissions Trading Authority (DEHSt) provides additional specificity on methodology application [18].

The M2 verification ecosystem comprises multiple accredited bodies operating under German Accreditation Body (DAkkS) oversight according to ISO 14065 standards and EU verification requirements [19]. These verifiers possess deep sector-specific expertise developed through years of auditing complex industrial facilities. The verification process follows a structured approach: strategic analysis assessing data flow risks, process analysis examining monitoring system maintenance and quality control, and data verification cross-checking reported figures against source documentation. This thoroughness ensures that verified data achieves high credibility in regulatory and market contexts.

M3 historical data continuity extends back to EU ETS Phase 2 beginning in 2008, providing over 15 years of verified emissions records for covered facilities. This longitudinal depth enables sophisticated baseline construction, trend analysis, and performance benchmarking. Facilities can demonstrate emissions trajectory over multiple compliance periods, supporting claims about improvement beyond simple point-in-time assertions.

4.3 Counterfactual Analysis: Would Germany's Architecture Emerge Without CBAM Pressure?

Understanding Germany's high-TM configuration requires distinguishing between EU ETS effects and potential CBAM-driven development. Germany's carbon accounting architecture predates CBAM by nearly two decades, suggesting that domestic and EU policy drivers, rather than trade pressure, shaped its development.

The counterfactual question: would a non-EU country facing similar industrial structure develop comparable infrastructure absent regulatory mandate? Evidence suggests not. Countries with advanced manufacturing sectors but without binding carbon pricing, including major Asian economies before recent policy shifts, did not independently develop equivalent verification ecosystems. The verification bodies, accreditation standards, and data infrastructure emerged specifically to serve EU ETS compliance requirements.

This observation carries implications for CBAM's convergence potential. If high-M development requires sustained regulatory pressure, countries lacking domestic carbon pricing face chicken-and-egg problems. Building verification capacity requires demand for verification services; demand requires regulatory requirements generating compliance obligations; regulations require political conditions enabling carbon pricing adoption. CBAM may accelerate this sequence by creating external demand for verification services, but the pathway remains longer than simple technology transfer.

4.4 Beyond Power: Steel, Cement, and Aluminum

German heavy industry demonstrates similarly high TM scores, though sector-specific characteristics create variation around the benchmark. Steel achieves high TM, with sophisticated carbon mass balance methodologies tracking material flows through integrated production routes [20]. The German Steel Federation (Wirtschaftsvereinigung Stahl) coordinates industry approaches, and facilities benefit from verification expertise accumulated through EU ETS participation.

Cement scores at comparable levels, reflecting engagement with Global Cement and Concrete Association protocols including the Getting the Numbers Right (GNR) database requiring detailed Tier 3 data on thermal energy, raw material composition, and alternative fuel use [21]. Heidelberg Materials and other major German cement producers participate actively in international sustainability initiatives requiring third-party verified carbon disclosure.

Aluminum demonstrates high TM with particular strength in perfluorocarbon (PFC) monitoring where German facilities have achieved substantial emission reductions. Trimet Aluminium's METRICS process control system exemplifies advanced integration of monitoring with operational optimization, enabling the smelter to function as a virtual battery adjusting energy consumption based on grid conditions while precisely tracking emission parameters [22]. The system records every anode effect occurrence with sufficient precision for Tier 3 PFC calculations.

5. China: Technical Excellence Meets Institutional Misalignment

5.1 Power Sector: High T, Constrained M

China's power sector presents the framework's most instructive case, demonstrating that Technology and Maturity can diverge substantially even within a single country and sector. The sector achieves high T scores, approaching Germany's benchmark, yet faces constrained M due to institutional arrangements misaligned with CBAM requirements.

The T1 monitoring coverage score reflects extensive CEMS deployment across Chinese thermal generation. Facilities above 20 MW capacity achieve approximately 96-98% CEMS coverage, with data transmitting automatically to provincial environmental monitoring platforms [23]. This deployment resulted from air quality regulation rather than climate policy, but the infrastructure serves carbon accounting purposes as well. Major utilities have integrated CEMS data streams with plant-level distributed control systems, enabling combustion optimization alongside compliance monitoring.

T2 digitalization has advanced rapidly, particularly among state-owned generators. China Electric Power Enterprise Federation member companies have widely deployed group-level carbon management platforms integrating fuel procurement, generation scheduling, and emissions monitoring [24]. Some platforms incorporate blockchain-based data verification responding to data integrity concerns from early ETS compliance cycles. These systems provide technical foundation for sophisticated carbon accounting, though their design reflects domestic rather than international requirements.

T3 methodology precision approaches German levels for major facilities. Large coal-fired units conduct batch-specific fuel sampling with laboratory carbon content analysis. Natural gas plants employ online gas chromatography for continuous fuel composition measurement [25]. Mass balance approaches tracking carbon through combustion processes achieve uncertainty levels consistent with Tier 3 requirements.

Yet M dimension scores reveal critical gaps. M1 standardization reaches moderate-to-high levels, reflecting comprehensive national standards including GB/T 32151 series for sectoral greenhouse gas accounting. However, these standards embed facility-level or enterprise-level accounting units designed for domestic ETS compliance, not the product-level boundaries CBAM requires [26]. A power generator reports annual emissions perfectly suited for domestic trading yet cannot directly produce per-MWh carbon intensity for specific export transactions without additional calculation infrastructure.

M2 verification ecosystem scores moderately high, with over 200 accredited verification bodies operating nationwide under CNAS oversight. These verifiers competently audit facility-level annual totals against Chinese standards. Their protocols do not, however, include product-level disaggregation procedures that CBAM verification would require. International verification firms with EU ETS experience offer parallel CBAM-specific services, but this dual-track approach increases compliance costs substantially [27].

M3 historical data continuity scores moderately. National ETS operation since 2021 and earlier provincial pilots provide roughly a decade of emissions data for major generators. However, this data exists primarily in facility-level aggregations. Reconstructing product-level historical intensities requires assumptions about allocation across output streams that introduce uncertainty.

5.2 The Accounting Unit Problem

The core T-M misalignment in Chinese power manifests as an accounting unit problem. Chinese carbon governance evolved serving domestic objectives including provincial allocation management and state-owned enterprise performance evaluation. Park-level industrial organization, where enterprises cluster in designated zones sharing infrastructure, reflects economic development strategies emphasizing agglomeration [28]. Carbon accounting at park or facility levels aligns with these governance logics.

CBAM demands different accounting units. Product-level carbon intensity enables EU importers to calculate certificates for specific goods. For electricity, this means per-MWh figures reflecting the carbon content of specific deliveries. Generating such data from facility-level systems requires allocation methodologies that existing infrastructure does not support.

The technical capability exists in principle. CEMS data captures emissions at sufficient temporal granularity to calculate hourly or even sub-hourly intensities. Generation metering records output at corresponding resolution. Dividing appropriately allocated emissions by corresponding output yields product-level intensities. The challenge lies in institutional infrastructure: standardized allocation methodologies, verification protocols for product-level claims, and data management systems maintaining the linkage between emissions and specific output streams.

Recent policy developments address this gap. GB/T 24067-2024 establishes product carbon footprint calculation guidelines explicitly addressing product-level boundaries [29]. Provincial pilots in Shanghai and Guangdong test implementation pathways allowing enterprises to generate product-level declarations from underlying facility-level data. These initiatives construct the interface layer connecting domestic systems to international requirements without replacing core arrangements.

5.3 Steel and Cement: Lower T, Comparable M

China's heavy industrial sectors score lower than power on both dimensions, though the pattern differs instructively. Steel achieves moderate TM with M slightly exceeding T; cement reaches similar moderate TM levels. Both sectors show M exceeding T, the reverse of the power sector pattern.

Steel's T1 monitoring coverage faces inherent complexity. Unlike power plants with centralized combustion, integrated steel mills involve dozens of emission sources spanning blast furnaces, basic oxygen furnaces, coke ovens, and sintering plants. Many sources generate fugitive emissions resisting continuous monitoring. CEMS deployment reaches perhaps 55-65% coverage concentrated at major stacks, with remaining sources estimated from activity data [30]. This partial coverage constrains overall T scores despite sophisticated monitoring at covered sources.

T2 digitalization varies sharply across the sector. State-owned leaders like Baosteel and Hesteel operate Manufacturing Execution Systems integrating production and environmental data. These platforms track material flows enabling carbon mass balance calculations. Smaller producers, particularly in regions like Hebei, rely substantially on manual record-keeping. This heterogeneity depresses sector-wide T2 scores even as leading facilities achieve international standards [31].

T3 methodology precision reflects the complexity challenge. Accurate steel carbon accounting requires tracking carbon flows through material balances: carbon enters through coke, coal injection, and limestone; exits in steel products, slag, and stack gases. Leading facilities conduct daily coke carbon sampling and maintain detailed iron ore chemistry logs. However, the material flow volume means some parameters rely on periodic averages rather than continuous measurement, placing precision at the Tier 2/Tier 3 boundary [32].

Cement T scores face different constraints. Process emissions from limestone calcination comprise roughly 60% of cement's carbon footprint, requiring raw material composition analysis rather than stack monitoring [33]. Current practice involves periodic sampling with laboratory determination of carbonate content. Roughly 40-50% of facilities conduct such analysis with Tier 3 frequency and precision. The remainder relies on industry averages or infrequent sampling introducing substantial uncertainty [34].

Both sectors score higher on M dimensions despite lower T, reflecting institutional development partially independent of monitoring infrastructure. National standards exist for both steel (GB/T 24234) and cement (GB/T 31222), providing methodological frameworks even where monitoring falls short [35][36]. Verification bodies have accumulated expertise through regional carbon trading pilots. However, the M scores remain moderate rather than high, reflecting implementation variability and verification capacity constraints outside major industrial centers.

6. Turkey and India: Contrasting T-M Configurations

6.1 Turkey: Cement's International Integration Versus Steel's Fragmentation

Turkey exhibits dramatic within-country sectoral variation that national-level analysis would obscure. Cement achieves moderately high TM with M exceeding T, while steel scores substantially lower with both dimensions depressed. This divergence reflects industry structure differences rather than policy variation, since both sectors operate under identical national frameworks.

Turkish cement benefits from concentrated industry structure and international organizational integration. The Turkish Cement Manufacturers' Association (TÜRKÇİMENTO) represents over 90% of national production capacity, enabling coordinated standards adoption [37]. Critically, major producers participate in the Global Cement and Concrete Association, implementing its Getting the Numbers Right protocol across member facilities. GNR establishes detailed Tier 3 methodologies for thermal energy consumption, clinker production, raw material composition, and alternative fuel accounting [38]. Çimsa Çimento's GCCA membership exemplifies this international alignment, with the company adopting global protocols that position it advantageously for CBAM compliance [39].

This international alignment elevates M1 standardization substantially. Turkish cement facilities follow globally harmonized protocols rather than developing domestic alternatives. M2 verification similarly benefits from international integration, with firms like SGS and Bureau Veritas maintaining Turkish operations with cement sector expertise [40]. The verification approach aligns closely with anticipated CBAM requirements, positioning the sector advantageously for compliance.

T dimension scores lag somewhat behind institutional development. Major producers have deployed sophisticated Manufacturing Execution Systems tracking production parameters relevant to carbon accounting [41]. However, not all facilities achieve comparable digitalization, and process emission monitoring through raw material sampling varies in frequency and precision.

Turkish steel presents a contrasting configuration. Production is more fragmented, with electric arc furnace mini-mills representing significant capacity alongside integrated facilities [42]. The Turkish Steel Producers' Association (TÇÜD) lacks the technical coordination role that TÜRKÇİMENTO plays for cement. Industry standards remain less developed, and verification expertise specific to steel production is thinner.

The T-M profile for Turkish steel shows both dimensions depressed. T scores reflect limited CEMS deployment outside major facilities and reliance on emission factor approaches rather than facility-specific measurement. M scores reflect weaker standardization and verification infrastructure compared to cement. Industry surveys indicate substantially lower rates of third-party verified carbon footprint certifications among steel producers compared to cement counterparts [43].

6.2 India: Aluminum Leadership, Steel Challenges

India demonstrates yet another T-M configuration, with significant variation across sectors reflecting corporate strategy as much as national policy. Aluminum achieves moderate TM with M slightly exceeding T, while steel scores lower with T slightly exceeding M. The aluminum pattern reflects deliberate corporate investments in institutional infrastructure exceeding domestic regulatory requirements.

Indian aluminum benefits from major producers pursuing international certification as competitive differentiation. Vedanta's Jharsuguda smelter achieved Aluminium Stewardship Initiative Performance Standard and Chain of Custody certification in 2024, becoming India's first facility meeting this rigorous benchmark [44]. ASI certification requires detailed carbon footprint accounting, third-party verification, and supply chain traceability aligning closely with CBAM requirements. This voluntary pursuit of international standards elevates M scores beyond what domestic regulation would produce.

The certification drive reflects market signals. European aluminum purchasers increasingly demand low-carbon products, creating price premiums for verified sustainable material [45]. Indian producers recognized that competing in premium segments requires meeting international standards regardless of domestic regulatory requirements. The resulting investments create M dimension capabilities potentially portable to CBAM compliance.

T dimension development in aluminum reflects the technical sophistication of major operations. Facilities like NALCO have pursued round-the-clock renewable energy procurement, combining solar, wind, and storage to provide continuous clean electricity addressing the sector's massive power consumption. The company targets 30% renewable energy by 2030, up from approximately 5% currently [46]. This strategy simultaneously reduces Scope 2 emissions and creates data streams supporting sophisticated carbon accounting. Monitoring of perfluorocarbon emissions from electrolysis has improved substantially, enabling Tier 3 calculations for these potent greenhouse gases.

Indian steel presents different challenges. Production occurs through multiple routes with varying carbon intensities: blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace for integrated mills, electric arc furnace for scrap recyclers, and direct reduced iron pathways using coal or gas as reducing agents [47]. This diversity complicates standardization, as different routes require different accounting methodologies.

T scores for steel reflect partial monitoring deployment, with sophisticated systems at major integrated producers but limited coverage at smaller operations. The prevalence of coal-based direct reduced iron, a relatively carbon-intensive pathway accounting for significant Indian production, creates accounting challenges distinct from blast furnace or EAF routes more common elsewhere [48]. M scores lag behind T, with verification infrastructure thin outside major exporters pursuing international markets.

The PAT scheme's energy efficiency focus has created technical capacity somewhat transferable to carbon accounting. Facilities accustomed to detailed energy monitoring can adapt systems for carbon purposes. However, the intensity-based framing of PAT differs from absolute emission tracking, and the normalization methodologies, while sophisticated, do not align directly with CBAM product-level requirements [49].

7. The Three-Layer Digital Divide

7.1 Beyond Hardware: Why Layer 2 and Layer 3 Matter

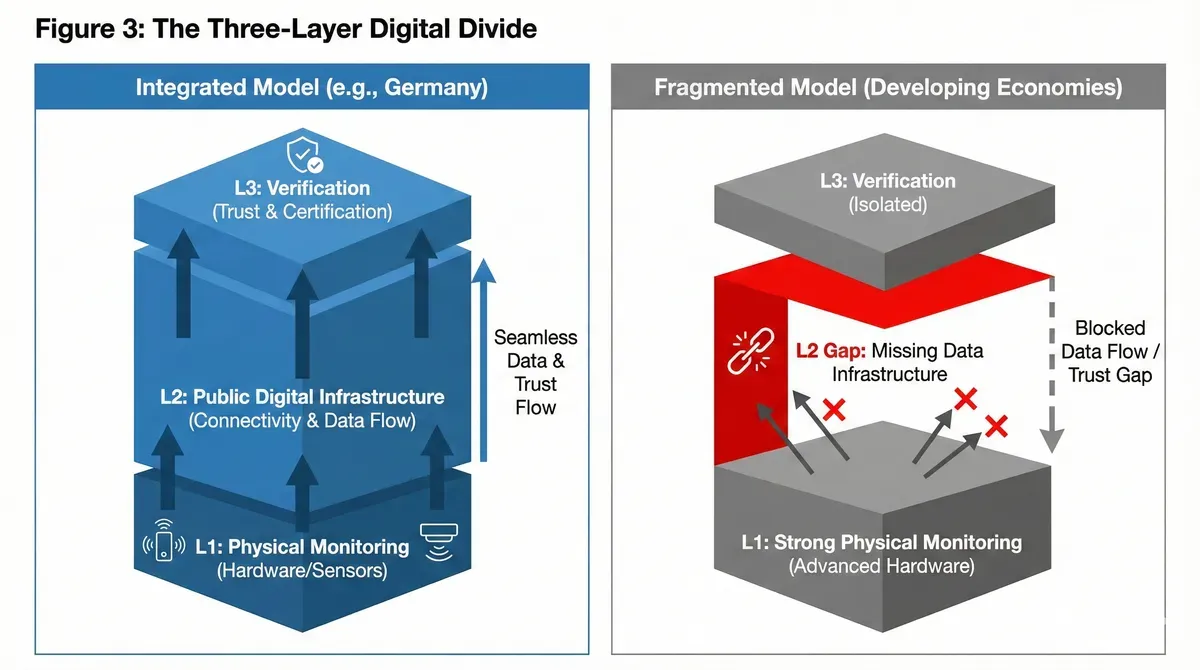

Cross-country comparison reveals a consistent pattern: Technology dimension gaps often concentrate at specific layers rather than representing uniform underdevelopment. Understanding this layered structure enables more precise diagnosis and targeted intervention.

Layer 1 encompasses physical monitoring infrastructure: the sensors, analyzers, and data acquisition systems generating raw emissions measurements. Development proceeds most rapidly because it primarily requires capital investment and technical installation. Countries can import monitoring equipment, train operators, and achieve substantial coverage within years given sufficient resources. China's power sector CEMS deployment demonstrates this trajectory, reaching 96-98% coverage through sustained investment and regulatory mandate [50]. Layer 1 represents the most tractable component of carbon accounting infrastructure.

Layer 2 encompasses data transmission and management infrastructure: the communication protocols, security measures, and platforms enabling data flow from source to destination. Development proves more challenging because it requires coordination across multiple actors and often benefits from public goods provision. Data transmission security, platform interoperability, and registry infrastructure exhibit network effects and economies of scale that private markets may underprovide. Germany's public investment in smart meter gateway standards and the MaStR registry created Layer 2 infrastructure enabling even small facilities to connect to centralized systems [51]. Countries lacking equivalent public infrastructure face fragmented private solutions with limited interoperability.

The Layer 2 gap helps explain why high T1 scores sometimes fail to translate into compliance capability. Chinese power plants possess excellent monitoring hardware generating high-quality data. However, this data flows into facility-level or enterprise-level systems designed for domestic purposes. Connecting these systems to international reporting requirements demands Layer 2 infrastructure that either does not exist or requires expensive bespoke development. The monitoring hardware works perfectly; the data cannot reach its needed destination in usable form.

Layer 3 encompasses verification and certification infrastructure: the institutions, protocols, and expertise validating emissions claims. Development requires the longest timeframes because verification expertise accumulates through experience. Training programs can convey technical knowledge, but competent auditing of complex industrial facilities demands accumulated judgment that takes years to develop. Germany's verification ecosystem reflects decades of operation, with verifiers who have examined hundreds of facilities across multiple compliance periods. Countries establishing new carbon accounting systems cannot simply purchase this capability; they must grow it through sustained practice.

7.2 Implications for Development Sequencing

The three-layer model suggests that development sequencing affects ultimate system performance. Different sequences produce different T-M configurations with distinct compliance implications.

A hardware-first sequence prioritizes Layer 1 deployment, achieving high T1 scores before Layer 2 and Layer 3 development. This approach generates monitoring data that may sit underutilized until transmission and verification infrastructure catches up. China's power sector exemplifies this pattern, with world-class CEMS generating data that existing institutional infrastructure cannot fully exploit for international compliance purposes.

A standards-first sequence prioritizes Layer 3 institutional development, establishing verification protocols and verifier capacity before comprehensive monitoring deployment. This approach means that when monitoring expands, verification infrastructure exists to validate resulting data. Turkey's cement sector partially reflects this pattern, with GCCA standard adoption preceding full monitoring sophistication.

A balanced sequence coordinates advancement across all three layers, ensuring that monitoring expansion coincides with transmission infrastructure development and verification capacity building. Germany's trajectory approximates this pattern, with EU ETS phases driving simultaneous progress across layers. However, the balanced approach requires substantial coordination capacity that not all governance systems can achieve.

No single sequence dominates all others. Optimal approaches depend on existing conditions, available resources, and strategic priorities. However, the framework clarifies that hardware investment alone, while necessary, proves insufficient for compliance capability. Layer 2 and Layer 3 development must eventually complement Layer 1 achievements.

8. Diagnostic Applications and Policy Implications

8.1 The TM Diagnostic Matrix

The framework's practical value lies in matching TM profiles to specific interventions. Different gap patterns require different remedies. A diagnostic matrix formalizes this matching, enabling practitioners to move from assessment to action.

Table 2: TM Diagnostic Matrix

| Configuration | Characteristics | Typical Case | CBAM Risk | Priority Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High T / High M | Advanced monitoring + mature verification | German power sector | Low: direct compliance feasible | Incremental optimization |

| High T / Low M | Strong hardware, weak institutional validation | Chinese power sector | High: "data without trust" | Standards alignment, verifier training, interface construction |

| Low T / High M | Robust institutions, limited physical infrastructure | Some Turkish steel | Medium: framework exists but data lacking | Equipment deployment, digitalization investment, Tier upgrading |

| Low T / Low M | Early-stage development across both dimensions | Many developing economy sectors | Very high: systemic capacity gaps | Sequenced comprehensive development |

High T / Low M configurations indicate strong physical infrastructure with weak institutional validation. Facilities can generate quality monitoring data but lack verification protocols or verifier access to certify the results. Interventions should focus on M dimension development: standards formalization, verifier training, and historical data accumulation through consistent reporting cycles. China's power sector exemplifies this configuration, where the primary need involves institutional interface construction rather than additional monitoring equipment.

Low T / High M configurations indicate robust institutional frameworks without corresponding physical infrastructure. Standards and verification capacity exist but facilities lack monitoring systems generating source data. Interventions should focus on T dimension development: equipment deployment, digitalization investment, and methodology upgrading from Tier 1/2 to Tier 3 approaches.

Low T / Low M configurations indicate early-stage development across both dimensions. Comprehensive capacity building is required, though sequencing choices arise. Prioritizing either T or M first, or pursuing balanced development, depends on available resources and strategic context. Many smaller developing economy industrial sectors face this configuration, requiring sustained multi-year development programs.

Balanced configurations with comparable T and M scores suggest that neither dimension severely constrains overall performance. Continued parallel development maintains balance while raising absolute capability. German sectors largely exhibit balanced high configurations, with incremental improvement across all components.

8.2 Sector-Specific Remediation

Beyond country-level diagnosis, the framework enables sector-specific intervention design. Different industries face characteristic challenges that generic capacity-building overlooks.

Power sector interventions in most contexts should emphasize Layer 2 and Layer 3 development given relatively advanced Layer 1 infrastructure. Priority actions include establishing product-level allocation methodologies enabling translation from facility totals to per-MWh intensities, training verifiers in EU MRR requirements, and creating data management platforms linking generation records to emissions monitoring.

Steel sector interventions must address both the complexity of multiple emission sources and the diversity of production routes. Priority actions include developing mass balance calculation standards appropriate for local production configurations, deploying sub-metering to improve emission source coverage, and building verification capacity specific to metallurgical processes.

Cement sector interventions should leverage global industry coordination through GCCA, which provides ready-made Tier 3 methodologies and data platforms. Priority actions include promoting GNR protocol adoption among non-participating producers, supporting raw material sampling frequency improvements, and connecting domestic verification to international certification frameworks.

Aluminum sector interventions must address both direct emissions from electrolysis (particularly PFCs) and indirect emissions from substantial electricity consumption. Priority actions include deploying PFC monitoring systems enabling Tier 3 calculations, establishing electricity sourcing traceability supporting accurate Scope 2 accounting, and pursuing international certifications like ASI that align with market and regulatory expectations.

9. Conclusion

This study develops and applies a Technology-Maturity framework decomposing carbon accounting capability into distinct dimensions that existing frameworks conflate. The Technology dimension, comprising monitoring coverage, data digitalization, and methodology precision, captures hardware and data infrastructure. The Maturity dimension, comprising standardization, verification ecosystems, and historical data continuity, captures institutional infrastructure. Together, these dimensions map the architecture of carbon accounting systems in ways that enable precise diagnosis and targeted intervention.

The framework's central insight is that Technology and Maturity follow independent developmental trajectories, a finding that challenges assumptions embedded in IPCC Tier systems and UNFCCC MRV frameworks. Countries can achieve high T with low M, or low T with high M, or various intermediate combinations. Each configuration generates characteristic compliance patterns and requires specific remediation approaches. China's power sector demonstrates high T with constrained M, possessing world-class monitoring infrastructure channeling data into institutional frameworks misaligned with CBAM product-level requirements. Turkey's cement sector demonstrates moderate T with higher M, with international standard adoption outpacing physical infrastructure deployment. These patterns would be invisible to analyses treating carbon accounting as unidimensional or assuming that technical precision automatically confers institutional credibility.

The three-layer digital architecture model further refines diagnosis. Layer 1 (physical monitoring) develops most rapidly through capital investment. Layer 2 (data transmission) benefits from public infrastructure provision that private markets may underprovide. Layer 3 (verification) requires sustained experience accumulation that cannot be accelerated beyond certain limits. Understanding which layers constrain particular systems enables targeted rather than diffuse capacity-building investments.

For practitioners, the diagnostic matrix linking TM profiles to specific interventions provides actionable guidance. High T / low M configurations need institutional development: standards formalization, verifier training, interface construction. Low T / high M configurations need infrastructure investment: monitoring equipment, digitalization platforms, methodology upgrading. Early-stage systems facing low T / low M must make sequencing choices reflecting available resources and strategic priorities.

For policymakers, the framework suggests that effective carbon accounting development requires coordinated advancement across hardware, standards, and verification rather than isolated investments in any single component. Countries that deploy monitoring equipment without corresponding institutional development may find sophisticated hardware generating data that existing systems cannot validate for international compliance. Countries that adopt international standards without physical infrastructure may have excellent protocols with nothing to verify.

The broader implication extends to global carbon governance. CBAM's effectiveness as a convergence instrument depends on trading partners' ability to generate compliant carbon data. This ability reflects TM profiles that vary systematically across countries and sectors. Understanding these variations enables more realistic assessment of compliance trajectories and more effective support for countries navigating carbon accounting development. The game has changed: as one observer noted, if IPCC era asked "can scientists calculate accurately?" and MRV era asked "did countries report completely?", CBAM era asks "can enterprises prove authentically?" The TM framework provides the diagnostic vocabulary for answering that question.

References

[1] European Commission. (2023). EU Monitoring and Reporting Regulation: Technical Guidance. Brussels: DG CLIMA.

[2] China Electricity Council. (2024). CBAM Compliance Challenges in Power Sector: Industry Survey Report. Beijing: CEC.

[3] European Commission. (2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/956 establishing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Official Journal of the European Union, L 130.

[4] Mehling, M. A., et al. (2019). Designing Border Carbon Adjustments for Enhanced Climate Action. American Journal of International Law, 113(3), 433-481.

[5] OECD. (2023). Effective Carbon Rates 2023: Pricing Greenhouse Gas Emissions through Taxes and Emissions Trading. Paris: OECD Publishing.

[6] IPCC. (2006). 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

[7] IPCC. (2019). 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Geneva: IPCC.

[8] Marlowe, J., & Clarke, A. (2022). Carbon Accounting: A Systematic Literature Review and Directions for Future Research. Green Finance, 4(1), 71-87.

[9] UNFCCC. (2018). Decision 18/CMA.1: Modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support referred to in Article 13 of the Paris Agreement. Katowice.

[10] Teng, F., & Zhang, X. (2010). Clean Development Mechanism practice in China: current status and possibilities for future regime. Energy, 35(11), 4328-4335.

[11] Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. (2024). National CEMS Deployment Report for Power Sector. Beijing: MEE.

[12] Unruh, G. C. (2000). Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy, 28(12), 817-830.

[13] German Federal Environment Agency. (2024). Continuous Emissions Monitoring Systems: Quality Assurance Requirements. Dessau-Roßlau: UBA.

[14] Bundesnetzagentur. (2024). Core Energy Market Data Register (MaStR): Technical Documentation. Bonn: Federal Network Agency.

[15] Federal Office for Information Security. (2024). Smart Meter Gateway Security Requirements. Bonn: BSI.

[16] German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. (2024). Redispatch 2.0 Implementation Report. Berlin: BMWK.

[17] VGB PowerTech. (2024). Best Practices for Fuel Analysis in Power Generation. Essen: VGB.

[18] German Emissions Trading Authority. (2024). Guidance on Monitoring and Reporting under EU ETS. Berlin: DEHSt.

[19] German Accreditation Body. (2024). Directory of Accredited Greenhouse Gas Verification Bodies. Berlin: DAkkS.

[20] Wirtschaftsvereinigung Stahl. (2024). Carbon Accounting in German Steel Industry: Technical Guidelines. Düsseldorf: WV Stahl.

[21] Global Cement and Concrete Association. (2024). Getting the Numbers Right Database: Methodology Manual v4.0. London: GCCA.

[22] TRIMET Aluminium. (2024). METRICS Process Control System: Technical Overview. Essen: TRIMET.

[23] Zhang, X., et al. (2020). High-resolution emission inventory of full-volatility organic compounds from cooking in China during 2010–2019. Scientific Data, 7, 358.

[24] China Electric Power Enterprise Federation. (2024). Digital Carbon Management Platforms: Industry Survey. Beijing: CEC.

[25] China National Petroleum Corporation. (2023). Natural Gas Quality Monitoring Standards and Practices. Beijing: CNPC Research Institute.

[26] Standardization Administration of China. (2015). GB/T 32151-2015: General Rules for Greenhouse Gas Emissions Accounting in Organizations. Beijing: Standards Press of China.

[27] China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals and Chemicals Importers and Exporters. (2024). CBAM Compliance Survey: Steel and Aluminum Sectors. Beijing: CCCMC.

[28] Wang, J., & Liu, Y. (2023). Industrial Park Governance and Environmental Policy in China. Journal of Chinese Governance, 8(2), 234-256.

[29] Standardization Administration of China. (2024). GB/T 24067-2024: Product Carbon Footprint Assessment Guidelines. Beijing: Standards Press of China.

[30] China Iron and Steel Association. (2024). Carbon Monitoring Practices in Chinese Steel Industry. Beijing: CISA.

[31] Baowu Steel Group. (2024). Digital Transformation and Carbon Management: Annual Report. Shanghai: Baowu.

[32] Zhang, Q., et al. (2024). Carbon Mass Balance Challenges in Chinese Integrated Steel Mills. Journal of Iron and Steel Research International, 31(3), 512-523.

[33] International Energy Agency. (2024). Cement Technology Roadmap: Carbon Emissions Reduction. Paris: IEA.

[34] China Cement Association. (2024). Process Emission Monitoring Survey Results. Beijing: CCA.

[35] Standardization Administration of China. (2009). GB/T 24234-2009: GHG Emissions Accounting for Iron and Steel Production. Beijing: Standards Press of China.

[36] Standardization Administration of China. (2014). GB/T 31222-2014: GHG Emissions Accounting for Cement Production. Beijing: Standards Press of China.

[37] Turkish Cement Manufacturers' Association. (2024). Sector Report 2024. Ankara: TÜRKÇİMENTO.

[38] Global Cement and Concrete Association. (2024). GNR Protocol Implementation Guide. London: GCCA.

[39] Çimsa Çimento. (2024). Sustainability Report: GCCA Membership and Low-Carbon Roadmap. Mersin: Çimsa.

[40] SGS Turkey. (2024). Environmental Product Declaration Verification Services. Istanbul: SGS.

[41] Oyak Çimento. (2023). Digital Transformation in Cement Production. Ankara: Oyak.

[42] Turkish Steel Producers' Association. (2024). Production Statistics by Process Route. Ankara: TÇÜD.

[43] Turkish Exporters Assembly. (2024). Carbon Footprint Certification Survey. Ankara: TIM.

[44] Vedanta Limited. (2024). ASI Performance Standard and Chain of Custody Certification Achievement. Mumbai: Vedanta.

[45] European Aluminium. (2024). Low-Carbon Aluminium Market Survey. Brussels: European Aluminium.

[46] NALCO. (2024). Round-the-Clock Renewable Energy Procurement Plan. Bhubaneswar: NALCO.

[47] Steel Authority of India. (2024). Production Route Carbon Intensity Benchmarking. New Delhi: SAIL.

[48] Joint Plant Committee. (2024). Indian Steel Production by Technology Route. Kolkata: JPC.

[49] Bureau of Energy Efficiency. (2024). PAT Scheme Normalization Methodology. New Delhi: BEE.

[50] Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. (2024). CEMS Coverage Statistics for Thermal Power. Beijing: MEE.

[51] German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. (2024). Digital Infrastructure for Energy Transition. Berlin: BMWK.

Authors

Alex is the founder of the Terawatt Times Institute, developing cognitive-structural frameworks for AI, energy transitions, and societal change. His work examines how emerging technologies reshape political behavior and civilizational stability.

U.S. energy strategist focused on the intersection of clean power, AI grid forecasting, and market economics. Ethan K. Marlow analyzes infrastructure stress points and the race toward 2050 decarbonization scenarios at the Terawatt Times Institute.

Maya is a communications strategist bridging technical modeling and public policy. She synthesizes research on grid modernization and decarbonization, ensuring data-driven insights reach legislators and industry stakeholders.